Who Wrote It?

Steve McGann | Wednesday Feb. 1st, 2023

Consciousness is what makes us unique, human. Language is the method we use to express that consciousness. Writing and reading the words of language are the concrete tools of the process. Whales and elephants and ravens have language, but they have no literature, at least none we have discerned. So we award ourselves a promotion above the rest of the lifeforms. Consciousness, which implies dominance; souls, which give the justification. But as we rocket through the 21st century, things have become confused. Computers, a human invention, have begun to blur the line between being a tool and an independent entity.

At a point in the last century, I completed grade school. I looked forward to a long summer of endless innings of pickup baseball and lying in the grass contemplating cloud shapes. This was not to be. In preparation for the next challenge, high school, my mother decided that I needed to master something called a term paper. The first step was to enroll in a typing class. This class had two very quantifiable goals: use all ten fingers on the keyboard, and type twenty words per minute.

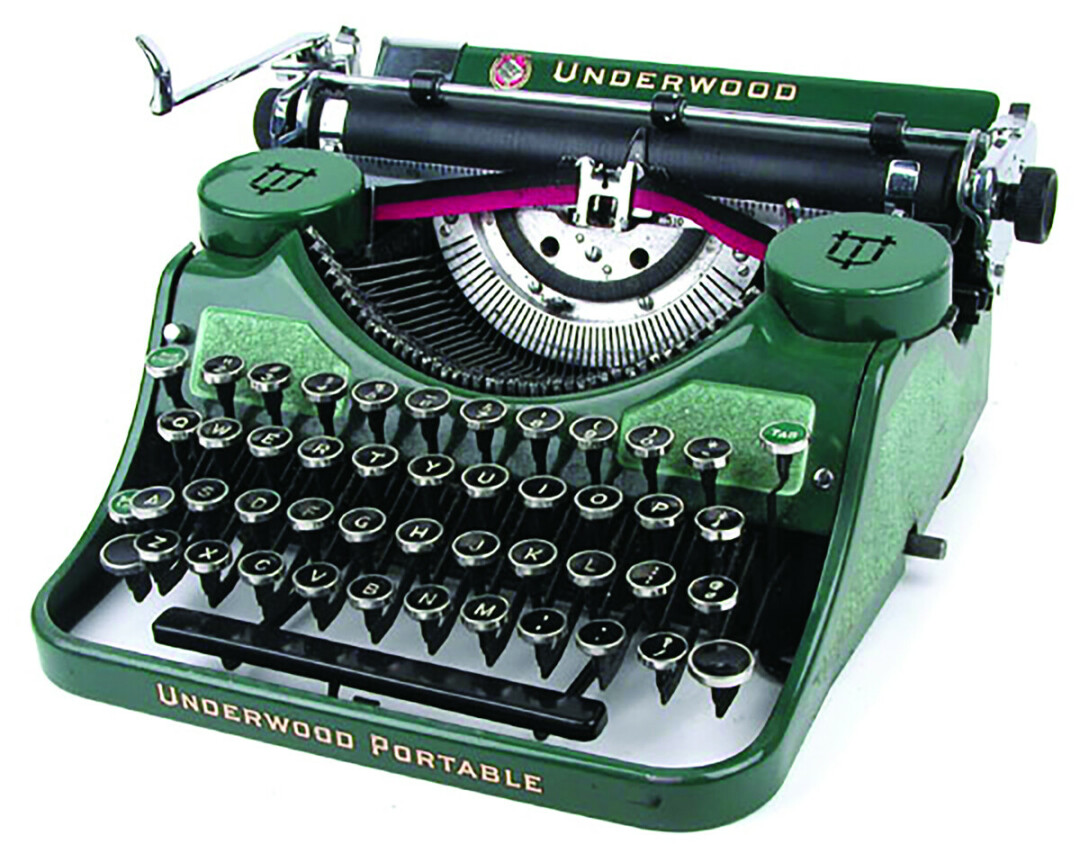

This was presented as the key to academic and lifetime success. I failed miserably. Our home typewriter, on which I was required to practice for an hour a day within sight and sound of the baseball lot across the street, was an old black Underwood. The mechanism for the key to strike the paper required a punch. One of the striker arms stuck there and had to be pried down. Two others tangled and struck together. They had to be bent a bit each day. Ink was transferred to fingers, then to keys, then to a scratch of my nose. Not pretty. The machines at the typing class lab had a sinister electric hum. There were no strikers, just a ball imprinted with letters buzzing around. The keypad could be activated by a breeze or a sneeze. Unable to switch between the sensitivity of the two machines, I was doomed.

I struggled along through high school and college until I found out that there were professional typists. I could not afford this service, but it somehow made me feel better. These were wizards who stroked the keyboard as if playing a sonata. Now, we have computers; word processors not only instantly forgive, they have eliminated the smudged, the crooked, even the white-outed paper! Typing is now nearly effortless. The only remnant I can think of from my long-ago class is that I still use most of my fingers. What does any of this have to do with consciousness?

The word processing programs that we all love and hate have become sophisticated. Not a simple keyboard any longer, the programs offer endless (needless) options of style, shape, font, sharing, and many other things. Hit the wrong key and things disappear or change completely. There is spellcheck, and what I call ‘commacheck.’ Yet, for all of these helping tools (or sometimes impediments) to word processing progress, the thoughts that power our fingers to strike the keys are our own. Human consciousness. Kinda.

There are now programs that aid our writing. Grammarly and Whitesmoke are two that go beyond spellchecking. They analyze and correct grammar, punctuation, and even word usage to make a person’s writing more concise and meaningful. Whitesmoke also offers plagiarism checks. Beyond these aids is a new generation of programs that perform the actual writing.

In 2017 a writer drove from New York to New Orleans, partially sponsored by Google. Ross Goodwin outfitted his vehicle with sensors hooked up to an AI computer that recorded and analyzed the journey. The car had a display similar to Google Maps, but produced prose rather than images. Pre-programed with twenty million words of poetry and literature, the AI wrote a narrative of the trip that was published without editing, titled, 1 The Road. The intent was to produce a novel akin to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road.

Author Truman Capote said of Jack Kerouac’s work; “That isn’t writing, it’s typing.” Reading excerpts of 1 The Road reminds me of Kerouac’s stream of consciousness style. Bursts of what could be called poetry are interspersed with the weather and GPS observations. This experiment was conducted just five years ago, as the first novel written by a machine. In the relatively short time since, AI writing has become much more sophisticated… more human?

Jasper is a leading AI-based writing program. Another is Rytr. The Jasper website claims that using their program will enable you to “Create amazing web content, video scripts, and blog posts,” among other things. Rytr offered a free trial. Why not? It states that the product will be “humanlike and high quality.” I watched an instructional video; most of the suggested uses were for business documents. The services provided were intended to create unique documents that would save time for a busy manager. My experiment with the app went a different way. I had recently read this poem by Dylan Thomas:

“I learnt man’s tongue, to twist the shapes of thoughts

Into the stony idiom of the brain,

To shade and knot anew the patch of words.”

The Rytr AI program required that several variables be chosen: language, tone, and case, or format. There were a couple dozen languages available. Tone offered choices from appreciative to worried. I chose thoughtful. The choices for case or format included emails, blogs, profiles, and product descriptions. There was nothing for poetry, so I chose song lyrics. The last variable was instructions. I asked for lyrics about transforming thoughts into language. Rytr wrote the following:

“I’ve felt a lot of things but I don’t know what to say Some moments I felt the world

But I don’t know who to say it to.”

Well, that is pretty awful. And yet, it did come up with something that fit my general request. When I specifically asked for the style of Dylan Thomas, it offered a completely different verse, which was fascinating—the program recognized Dylan Thomas and wrote an interpretation of his style. I pushed forward and added that it adopt a sonnet form. The result was again completely different, but had neither the form nor the rhyming pattern for a sonnet. Dylan Thomas did write sonnets, but that combination confused the AI app. It is interesting that a small change in the directions produced completely different text. At this point, I had used up about half of the allotment for the free trial. It would be fun to play with but I am not ready to purchase the app. The key to the creation of content seems to lie in the specificity of the written directions.

AI has become indispensable for scientists and academics for research and literature reviews. But what about students writing for grades? The old term paper. A just-released online tool called ChatGPT has caused fears of cheating among professors. Some have said that AI writing tools will signal the end of trusting student writing, or a return to handwritten tests. Cursive is back? Other professors are excited to work with their students to explore the possibilities of this new technology. Of course, as soon as this tech is available, someone will develop an app to detect whether an AI program wrote an essay.

What is the balance for these tools? Can a writer take credit for the output of an AI powered writing app when they simply gave some directions? You can pedal an electric bicycle, but it will provide a burst to pull you up a hill. For athletes, vitamins and nutritional aids are acceptable, but performance enhancing drugs are not. For that matter, writers have for centuries used alcohol either to speed up or slow down their brains. Where is the line between natural and artificial? What is acceptable in the ethics of writing? The best-selling author James Patterson employs ghost-writers and credits them in his books. Would his books sell as well if his ghost-writer were a machine? Are these AI tools the equivalent of gateway drugs? Will they become permanent substitutes for human creativity?

If I could have programmed Rytr to produce a 1500 word article that would be acceptable for Bozeman Magazine, I may have done so just to see the result. But that result, which does not seem quite possible yet, would require much more knowledge, both from the app and myself. I wrote this article alone, although in an email the Rytr people had promised me writing superpowers. It is easier for me to form a few thoughts on my own than it is to decipher, understand, and use new technology. I might as well be pounding away on the old Underwood.

If you would like to be recognized for your writing craft, email a relevant submission to info@bozemanmagazine.com by the 10th

of the month for publishing consideration.

| Tweet |