Breaking Down Barriers: Lizzie Williams A Black Entrepreneur of Early Bozeman

Crystal Alegria | Wednesday Feb. 1st, 2023

An early Bozeman resident who should have a place in our local historical narrative but does not is Lizzie Williams, a Black woman who lived in Bozeman from 1869 to 1875. Though tragic, her story tragic is at times heart-warming, and always compelling. This is not a story that has been widely heard, as the history of Lizzie Williams’ life has only recently been uncovered. Through the examination of many historical documents, her life story is coming together piece by piece, but it is not complete. There is still much more to learn about the life of Lizzie Williams, but this is a start.

Lizzie Williams, also referred to as Elizabeth, was born in Louisville, Kentucky around 1834. She worked as a hospital nurse in her early life, but by the early 1860s she had made her way to Central City in the newly formed Colorado Territory, where she married James N. Williams in 1862. James, also Black, worked as a barber in Central City, and Lizzie helped him in his barbershop. The couple moved to Denver in 1864, where they opened the Star Barber Shop.

As context, while Lizzie and James lived in Colorado Territory, the Civil War raged in the East, and gold was discovered in what would become Montana Territory. Most likely, both Lizzie and James would have moved to Colorado Territory because of the discovery of gold there in 1858. We can speculate that Lizzie and James, like many others at the time, heard rumors of gold discoveries in the newly formed Montana Territory. They joined the rush to the booming new territory, leaving Denver in June of 1865. In April of 1865, just two months before the Williams’ departure from Denver, Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia. About the same time Lizzie and James were traveling West to Montana Territory, all those still enslaved in Texas were notified of their freedom on June 19, 1865. This is now nationally recognized as the Juneteenth holiday.

Lizzie and James established themselves in Helena, where James opened a Tonsorial Parlor (the historical term for a place to receive a shave and a haircut) on Helena’s Bridge Street, which was a raucous place. This street epitomized the “wild west” in its truest form, with mud and the smell of manure a constant. But the money was flowing, so that’s where James and Lizzie wanted to be. The chaos of a boomtown atmosphere created a perfect opportunity to make a good living.

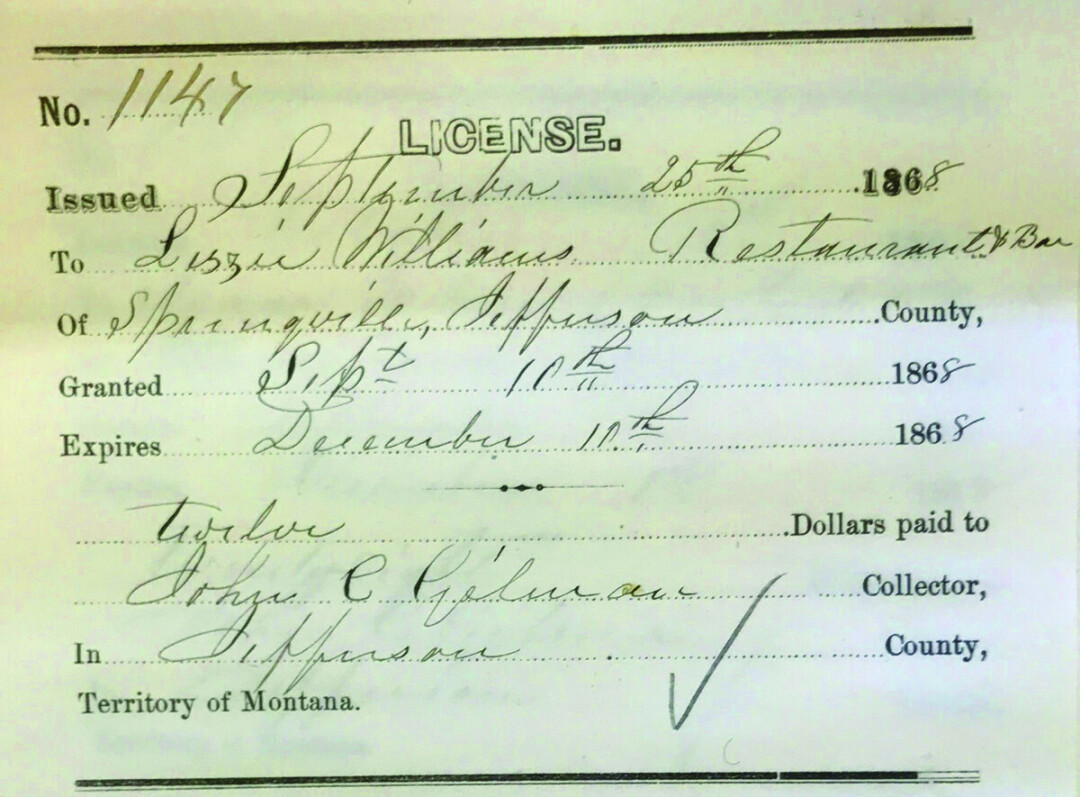

As 1868 dawned, there must have been trouble between Lizzie and James that could not be resolved. Lizzie moved to Springville, Montana Territory without him. She purchased a business license for a restaurant and bar in Springville on September 11th, 1868 in her name only. For unknown reasons, James deserted Lizzie in July of 1869, leaving her and the Montana Territory for good.

Springville was a small town located near present-day Townsend, Montana. It was one of the many small mining camps that sprung up as people were testing the ground for gold and other minerals to mine. Springville was first known as Hog-Em, because the miners who arrived found that a few men had “hogged up” the paying claims in the area. The post office was active from 1869 to 1879, but it was never a large town. Lizzie must have seen the writing on the wall for Springvillle, knowing the small town was not going to survive, because she moved to Bozeman in the fall of 1869.

When Lizzie Williams came to Bozeman, the town was still in its infancy, having only been established in August of 1864. At the time of Lizzie’s arrival, Bozeman had a population of about 400 people but was growing rapidly. There was talk of the railroad coming through in 1873 (it did not actually come through until 1883), and the need for her services as a cook and hotelier were desperately needed.

She wasted no time in obtaining property to set up her restaurant and lodging house. In January of 1870 she purchased a lot and building on Main Street for $2,200 and on January 30th purchased a business license for fifteen dollars to operate The City Restaurant and Hotel. She bought the building and lot from George Dow, who had been deeded the property by George Frazier. George and Elmyra Frazier had built this hotel in 1866 with partner John Bozeman, and had run it as a hotel, restaurant, and tavern until they sold it to George Dow in November of 1869.

In March, Lizzie posted a notice in the local newspaper, the Montana Pick and Plow stating, “CITY RESTAURANT, re-fitted, re-opened, & re-finished. Mrs. Lizzie Williams, former proprietress of the Southern Hotel, Springville, will be pleased to see all her old customers and the public generally. The table will be supplied with all the delicacies of the season and every attention shown to all patrons.” Lizzie was now set up in Bozeman, running a restaurant and hotel on Main Street, but she didn’t stop there. In 1872, the Avant Courier newspaper tells us that Lizzie had a wood-frame building built on her lot, which she rented out to a Mr. Merkle, who opened a jewelry store.

After coming to Bozeman, Lizzie established a business partnership and friendship with Samuel Lewis. Lewis was of Haitian descent and had come to Bozeman about the same time as Lizzie. Samuel Lewis had spent his childhood in the West Indies but came to the United States as a boy. His parents both died in the 1840s, leaving Samuel and his younger sister, Edmonia, to be raised by family. As a young man, Lewis heard of the California gold rush and moved to San Francisco, where he worked as a barber for two years. He then traveled the world until he landed in Montana in 1866. He spent time in Virginia City, Helena, Radersburg, and Elk Creek, plying his trade as a barber, and also as a sleight-of-hand performer and musician. All the while, he was supporting his sister Edmonia from afar, eventually seeing her settled at Oberlin College in Ohio. After settling in Bozeman in 1869, he opened a barber shop adjacent to Lizzie’s property on Main Street.

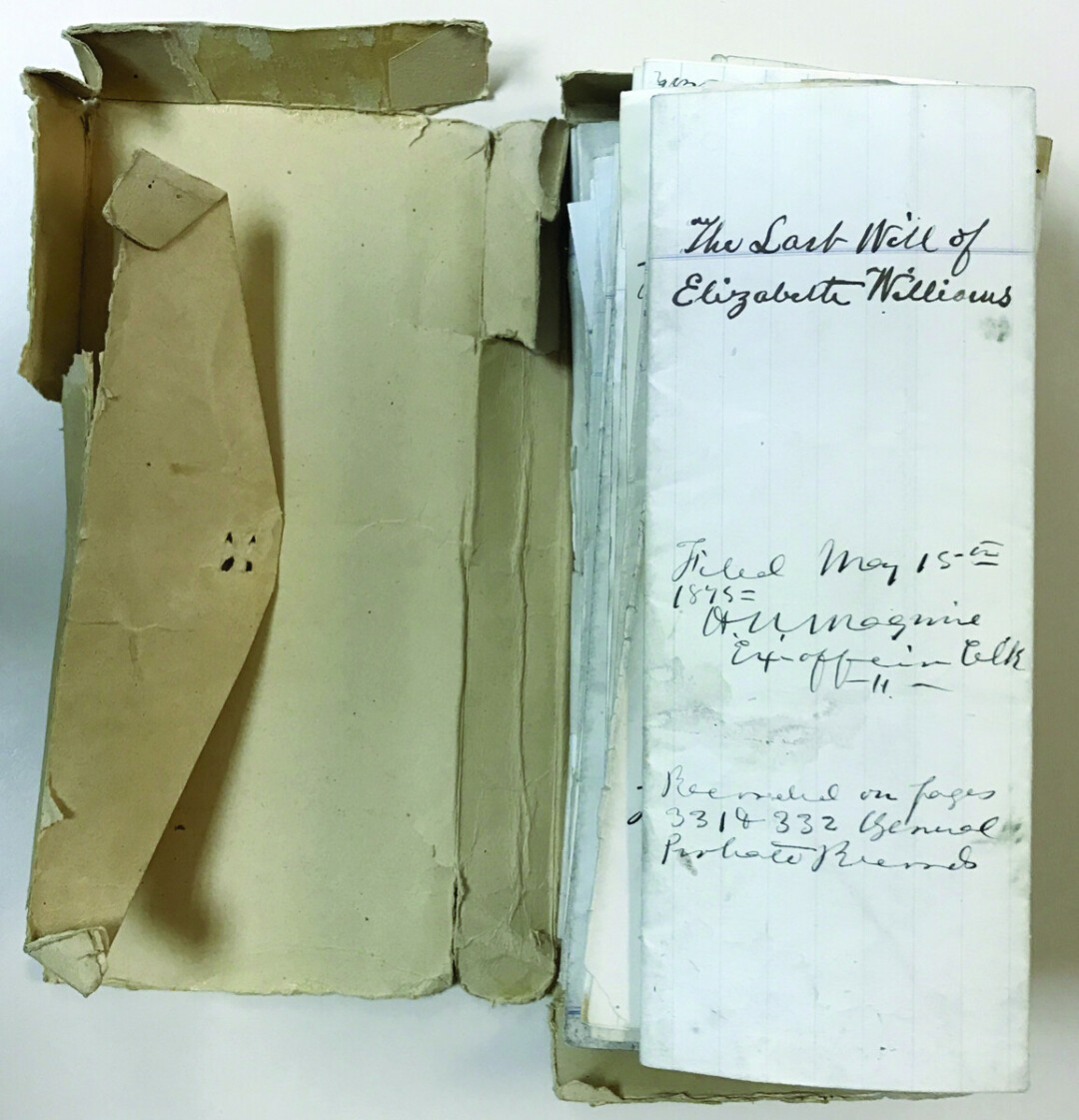

By 1874, Lizzie had accomplished quite a bit in her (approximately) 40 years but as this year dawned, she must have known something was not right with her health. She was sick, and it was probably a sickness she was not going to recover from. On June 18, 1874, she filed for a legal divorce from James Williams and on July 14, she sat down in the presence of three witnesses (Lester Willson, Horatio Maguire, and Joseph J. Davis) and wrote her last will and testament.

Lizzie died on April 26, 1875 at the young age of 41 or 42. According to probate records, she was worth $3,823.11 when she died, a goodly sum at that time. Lizzie named Samuel Lewis as the executor of her will. After her death, Lewis paid Lizzie’s remaining bills, funeral costs, and then distributed the remainder of her wealth to two people. One of the recipients was Lizzie’s estranged daughter, Rebecca Brown, who lived in St. Louis, Missouri. The second recipient was none other than Samuel Lewis’ sister, Edmonia Lewis. After her time at Oberlin College, Edmonia had become a world-famous sculptor and was living in Rome, Italy. It is doubtful that Lizzie ever met Edmonia, but most probably it was Samuel Lewis’ influence that brought about this inheritance.

Lizzie William’s obituary is a testament to her life, stating; “The loss of Mrs. Williams is deeply and universally deplored in Bozeman, where she had endeared herself to almost every family by invaluable services rendered in seasons of sickness — being ever ready to answer such calls from rich and poor alike. By her natural kindness of heart and former experience as a hospital nurse, she brought sunshine into all the sick rooms she visited. She was fully reconciled to the change, being conscious almost to the last, and assuring her friends, with her last audible breath, that she knew she was an heir of immortality.”

There is still much to learn about Lizzie Williams, not only about her time in Bozeman, but also her life in Central City, Colorado, and her earlier years in Kentucky. We know almost nothing about her daughter, Rebecca Brown, other than that she did come to Bozeman and retrieve the property items left to her by Lizzie. Most likely, Lizzie Williams has descendants living today — that research and discovery is still to come. In her short time here in Bozeman, she made an impact, and her name can be found scattered through historical documents recounting her as a woman of character, kindness, and charity. As a Black woman living in the west in the 1870s, her life was not easy. With many confederate sympathizers living in Bozeman at that time, racism was most likely a daily part of Lizzie’s life. She overcame many obstacles to live as a land-owning, business-owning, independent Black woman in Montana Territory. Let’s collectively remember her name and weave it back into the history of Bozeman, in remembrance of a life well-lived.

| Tweet |