Drunk and Disorderly: The Era of Prohibition

Kelly Hartman | Wednesday Sep. 1st, 2021

As those living in the Gallatin Valley endure this exceptionally hot summer, one could hardly imagine doing so without the help of a cold beer or a refreshing cocktail. However, that is just what those living exactly one hundred years ago in the prohibition era of 1919-1926 had to do. Moonshine was the only beverage of the day, taken at a considerable risk of law breaking and potentially deadly consequences due to subpar brewing methods.

Montana voters approved the state-wide prohibition of alcohol in November of 1916, with laws being put into action in December of 1918, two years before the National Prohibition laws took hold. This was due in a large part to the efforts made by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Montana would also be early in its repeal of the anti-liquor laws, being the first state to vote for an end to prohibition in 1926. Nationally, Prohibition would be repealed in 1933.

From 1919 to 1926, over 250 persons were arrested for prohibition violations in Gallatin County. Violations included possession, selling, manufacturing, and the transportation of moonshine or intoxicating liquors. There were also many arrested for being drunk and disorderly which usually led to a $10 fine and a night in jail to sleep it off. Any of the aforementioned violations, however, carried a much steeper fine. Possession most often constituted a $100-$150 fine, while the manufacture, selling or transportation of moonshine could bring about a $300-$900 fine and jail time of 3-6 months in most cases. Most of the offenders were men, with less than 5 women being jailed during this time for prohibition violations.

Gallatin County Sheriff James Smith came into office late in 1922. During his campaign, it had apparently been circulated that he both sent moonshine to threshing crews for votes and had been continually intoxicated during the seven years he had lived in Bozeman. This rumor led Smith to place a statement in The Bozeman Avant Courier: “I believe in a dry town and county. I believe in enforcing the laws of the state, not as they might be interpreted, but as they are written. If elected to the office of sheriff I will use every effort in my power to suppress the moonshining and bootlegging that may be going on in Gallatin County.”

And he was as good as his word. During the next few years, the department under the guidance of Sheriff Smith would conduct a number of major raids to catch those in the act of making moonshine. Some finds, however, would be accidental, as such was the case on the night of April 24th when a speeding car was stopped by the sheriff’s force. In the car were Claude Solt and Charles Smith along with 40 gallons of moonshine. Both men were arrested for possession and transportation of liquor. Solt would spend 40 days in jail and pay a $200 fine. Charles Smith however was released after 18 days being discharged by Judge Law for a lack of evidence. A fine could be served out in a $2 a day stay at the Gallatin County Jail.

In most instances, the confiscated moonshine was brought to the jail to be used as evidence in the arrestee’s trial. In this instance, however, the 40 gallons of contraband taken from the car was poured down a manhole near the courthouse. It was noted that a “thirsty crowd” watched the scene and that “scarcely had the officers finished their unwelcome task when two autos collided almost over the spot where the booze was destroyed.” The paper posed the question “were the fumes that strong?”

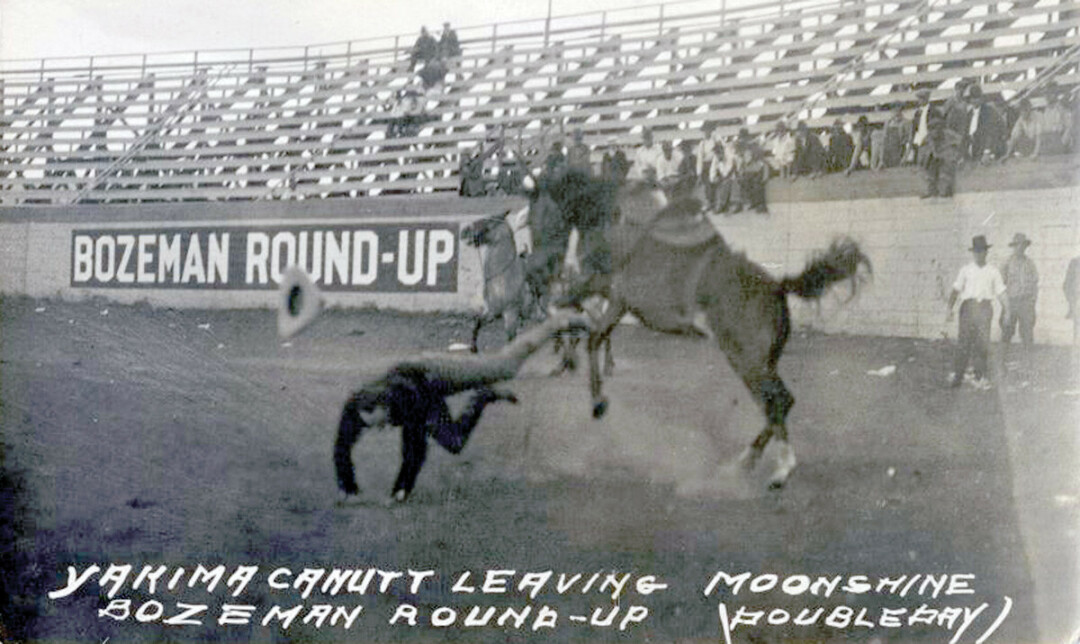

At the first Bozeman Roundup during Sheriff Smith’s reign, the force made a show of putting down the event as the “cleanest in the history of all roundups.” As a result of their efforts, 11 men were arrested for possession, transportation and selling of moonshine. In one instance, a 75 gallon still, 19 barrels of mash and 50 gallons of moonshine were confiscated from a local ranch. The Bozeman Courier was prompted to state that “Smith Takes ‘wild’ Out of Roundup.” Ironically, the winning horse of the bronc riding event was named “Moonshine.”

The County Sheriff’s Department was not the only one to be working overtime to enforce the National Prohibition laws. The City Police Department was also hard at work. On March 6, 1923, City and County officials raided Ponsford Place, a soft drink stand. The place had been staked out for days until a drunken man was picked up and questioned and it was discovered he had obtained liquor from the stand. When the place was searched, moonshine was discovered in several fruit jars, a teakettle and on the person of Mr. Galbraith, proprietor.

The manufacture of moonshine was not always a sanitary endeavor and could prove dangerous. In 1924, a man’s chickens were killed after having partaken of wet mash that had been dumped out by officers in a farmyard. The Bozeman Courier noted, “that the average distiller of the average moonshine product can drink his own liquor after knowing the filth of which the fermenting mash is composed, seems almost an impossibility.” In a raid in nearby Livingston in Park County, the decomposing bodies of drowned mice had been found in the bottom of barrel full of mash. Gallatin County doctors stated that the slightest presence of copperas (a green sulphate mineral) in the neck of a still could cause serious damage to the drinker. At the time, it was said there was a confiscated still in the basement of the County Jail with enough copperas to “kill an entire regiment of moonshine drinkers.” It is hard to determine just how often those manufacturing the substance succumbed to these hazards.

In 1932, William L. Ford, age 26, died from burns received when his 25-gallon keg of moonshine exploded in front of him. The burns had covered his body from the waist up and worse, fumes and steam had entered his lungs as well. Ford had been attempting to age the liquor with an electric device manufactured for that purpose when there had been a malfunction resulting in a spark that had ignited the liquor. When the keg had exploded, the liquor had landed on Ford and immediately caught the man on fire. His wife had attempted to put out the flames, but had herself become badly burned, although she would survive.

In February of 1925, Sheriff Smith made a public return on the department’s recent successes in upholding Prohibition. According to Smith, his force had seized about 13 gallons of moonshine, not a huge amount by any means. However, they had managed to find and destroyed over 19 partial to complete stills. In the case of more than one still, including one in the Sedan district, dynamite was used to blow up the operations as they would have been too difficult and costly to bring into the county jail for evidence. The department also burned down several cabins in many of the canyons about Gallatin County in hopes of deterring would-be moonshiners from setting up their operations there. Overall, it was noted that the copper from all these stills, weighing 400 pounds, was sold for $24.00.

In 1926, the state of Montana voted to end Prohibition. While this did take effect, the Bozeman Police Force was in no way becoming more lenient. According to a notice in The Bozeman Courier, November 12, 1926, Judge Wilson saw reason keep up a strict attentiveness to the liquor trade. Judge Wilson stated: “Hitherto, in Bozeman, we have been arresting and punishing ‘bootleggers’ and ‘moonshiners’ as having violated a city ordinance which declares the liquor traffic to be a nuisance. We see no reason for changing or modifying that policy. Such traffic is still a nuisance that may and should be punished under the quite large police powers granted to cities by the general laws under which cities are organized and operate.” He then went on to list a few city codes, such as Subdivision 33, “to define and abate nuisances, and to impose fines upon persons guilty of creating” a nuisance and Subdivision 25, “to prevent and punish intoxication, fights, riots, loud noises, disorderly conduct, obscenity and acts or conduct calculated to disturb the public peace.” According to Judge Wilson: “There is nothing more productive of the foregoing offences than the liquor traffic. How shall we prevent such offences if no attempt is made to control and suppress the liquor traffic?”

Times changed, and today alcohol is a booming business in the Bozeman area, particularly in the growth of new breweries and distilleries. Let’s drink a toast to those who endured the dry spell of the roaring ‘20s!

| Tweet |