Sedition in Gallatin County

Sugar, the Kaiser and Two Years Imprisonment

Kelly Hartman | Monday May. 1st, 2017

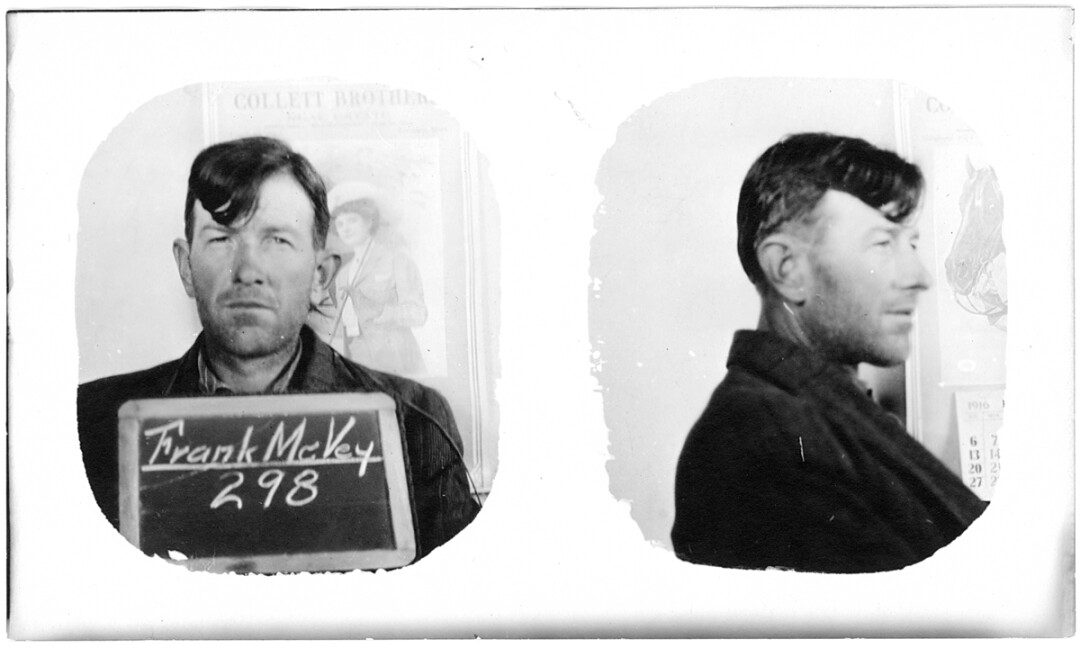

On April 11, 1918 Frank McVey, a laborer from Illinois, stepped into a Logan restaurant, about 25 miles from Bozeman. His complaint about sugar and a comment in support of the Kaiser landed him in the local jail. He would spend the next three years of his life in the State Penitentiary, convicted of sedition.

When the United States entered the Great War in 1917 it had already missed out on the first three years of battle because of a reluctance of the government and its citizens to participate in an overseas conflict. Since the beginning, however, private donors had been sending monetary donations and food to help those in need; in fact America was the top philanthropic nation at the time. The government, upon entering the war, found it necessary to discourage anti-war sentiments in order to bolster public support of their involvement. The industry of public relations would be born during this decade of pro-war, patriotic propaganda. Never before had the nation’s citizens had a calling quite like this to do their part, which included keeping an eye out on your neighbor to be sure they too were lending a hand, or at least not condemning the effort.

“Slacker,” was a term commonly used during World War I to describe a person not participating in the war effort, particularly those avoiding military service. “Slacker raids” were made in an attempt to find evaders. While this term was not used across the pond in Britain, women in the Order of the White Feather addressed such perceived evasion of “duty”. This group handed out white feathers representing cowardice in an attempt to force men, and in many cases young boys, into service through guilt. In America during this time, “slackers” could be arrested and made to serve time or register for military duty if found guilty of evasion. In Bozeman, from the United States early involvement in WWI to the Armistice in 1918 nine men were arrested for this offense. Closely related was a “failure to register,” another common offense. In total 18 men were held under investigations pertaining to wartime evasion. Five of these men were found either too young to serve or not fit for military service, one paid a $10 fine and the remaining 12 either registered or were taken to a local military outpost where it is presumed they committed to doing their duty. Also there were found 13 cases of military desertion found in the Gallatin County Jail records.

Among “slackers” and deserters was another group of offenders, those who spoke or took action against either the government or the war efforts. The Espionage Act of 1917 followed closely by the Sedition Act, passed May 16, 1918, resulted in citizen promoted policing of neighbors. The attempt of the government to keep the people of the United States united in the war effort led to an overall panic of the people who feared their neighbors could be German sympathizers. This fear would escalate during WWII and the era of McCarthyism where in many cases the system led to an abuse of the law by those who sought to endanger those they disliked by claiming them unpatriotic In Bozeman, twelve men were arrested for seditious behavior or remarks; four were found guilty. Two men would be sent to the State Penitentiary, one being Frank McVey.

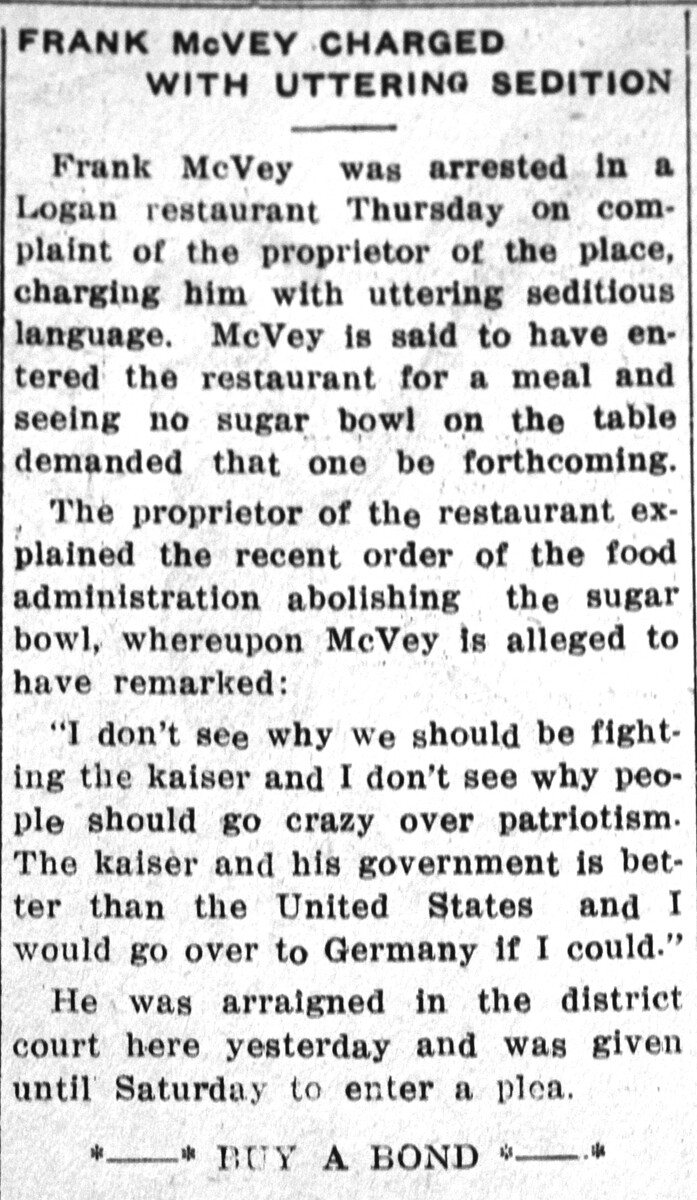

Frank was first arrested on April 11, 1918. The Bozeman Weekly Courier of April 17th printed a small article titled “Frank McVey Charged with Uttering Sedition” that described the scene that led to his arrest. It seems that McVey had entered a restaurant and seeing that there was not a sugar bowl on the table “demanded that one be forthcoming.” The proprietor told him that the food administration had abolished the sugar bowl in an effort to conserve supply, something that McVey found displeasing. According to the Courier, McVey “brought a sack of sugar from his pocket from which he put a liberal allowance in his coffee.” Proprietor C.S. Hopping and a patron, C.W. Clary prevented his drinking the coffee. During the commotion he was alleged to have remarked: “I don’t see why we should be fighting the kaiser and I don’t see why people should go crazy over patriotism. The kaiser and his government is better than the United States and I would go over to Germany if I could.” He was promptly arrested; the Jail record stating a warrant was made out for the offense of sedition. However, it appears that on May 16th, 1918, while McVey was in custody, an additional warrant was completed on a complaint by Lee B Anderson that McVey had unlawful possession of a firearm. It is unclear which warrant held him in jail, but he remained at the Gallatin County Jail until his court date. The trial was held June 3rd and it took only 10 minutes for the jury to bring back a verdict of guilty. On the same day Frank Waara was also tried for sedition, they were both found guilty and taken to the Montana State Prison on June 7th. Their convictions made statewide news as reported in the Montana Record-Herald, “Two Men are Sentenced to Prison for Sedition.” Waara served 11 months of an 18 month to 3 year sentence and McVey 26 months of a 2 to 4 year sentence. By World War II McVey was living in Pasco Washington, unemployed at the age of 63.

Of the 43 arrests in Gallatin County related to WWI made between February 1917 and August 1919, Waara and McVey were the only two who served longer than a short jail sentence illustrating the severity of being found guilty of sedition.

Montana’s sedition law preceded that of the National government. With the efforts of Montana’s Senators, Congress passed a Sedition Law 3 months after Montana with only 3 words changed. Readers with a further interest in this subject should read “Darkest Before the Dawn” by Clemens P. Work. On May 3, 2006 the 75 men and 3 women sentenced for sedition in Montana were pardoned. The Gallatin History Museum (housed in the old County Jail) has Frank McVey’s story as well a new World War One exhibit on display.

| Tweet |