Bozeman Women that Made a Difference

Politics, Poultry N’ Pottery

Cindy Shearer | Tuesday Mar. 1st, 2016

Mabel Van Meter Cruickshank and her carpenter husband Pete settled in Bozeman in 1899; Mabel was 27. In Bozeman she reared their two sons, James and John, and found time to go back to school at Montana State College subsidizing their family income by teaching beginning piano lessons.

Mabel was described as small, plumpish and quiet, a no-nonsense dresser and not one to bring attention to herself. She also was the driver in the family and was often seen driving down the middle of the road at high rates of speed in the large family car with Pete, her husband, in the backseat.

Not content to only be a homemaker, Mabel searched out opportunities in the community to participate. She was active in the Presbyterian Church, Eastern Star, and in the Women of the Shrine. During World War I, she supervised the making of surgical dressings for the Red Cross and joined the Business and Professional Women’s group and served on its state legislative committees. She worked hard in local Democratic politics and became a state committeewoman for Gallatin County.

In 1928, Mrs. Cruickshank became president of the Women’s Club of Bozeman, now at the height of its power. One of her concerns was the lack of any zoning commission in Bozeman; construction, she felt, was helter-skelter and there was no protection for existing land use. Just before Christmas in 1929, Mrs. Cruickshank and other club members notified the city commission that they expected an immediate draft to establish a zoning commission. This being a demand rather than a request of the Women’s Club, the commissioners moved to establish a zoning ordinance in spring 1930.

Females had appeared in state office before but were rare and in 1936 Mabel Van Meter Cruickshank decided to run for the Montana Legislature, the first woman in Gallatin County to do so. She raised no campaign funds and printed no handbills. In her opinion such things were foolish expenditures. The Democratic Party officials did place a slate ad in the local paper during the campaign that assured voters that candidate Cruickshank had not forsaken her homemaking role, “a task she has never stinted”. As a result of her involvement over the years with so many local organizations, it was not surprising that Mabel Cruickshank at age 64 easily secured the votes to go to Helena.

While in Helena, Mabel sponsored Bill 233 to establish adult education schools or classes throughout the state. It passed, but her Bill 232 to establish nursery schools and kindergartens in Montana did not. Her political career ended when husband Pete suffered a heart attack in July 1938 and she returned home from Helena to care for him.

Mabel passed away in 1965 and is buried in Sunset Hills Cemetery; her tombstone reflects her life as it is unadorned and simply states her name and year of birth and death. In 1989, a tree was planted in her name in Kirk Park and a shelter named after her to memorialize the first woman to win election to represent Gallatin County in the Montana Legislature.

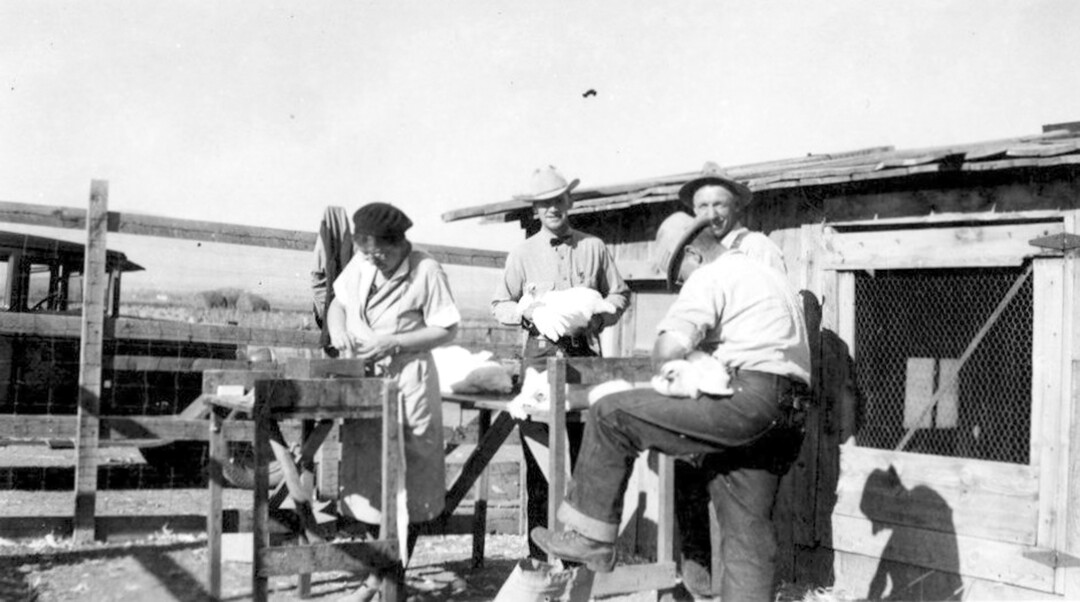

In 1922, the Extension Service at Montana State College in Bozeman hired Harriette Cushman to be Montana’s poultry specialist. Harriette Eliza Cushman was born in Alabama in 1890 and graduated from Cornell University in 1914 with a degree in bacteriology and chemistry. In 1918 she earned a poultry specialist degree from Rutgers University and became one of the few women to pursue a career as a poultry scientist.

Under Cushman’s guidance, the poultry industry in Montana expanded significantly as a result of creating cooperative marketing practices. Cushman helped form the nation’s first egg and turkey wholesale cooperatives, enabling Montana growers to negotiate top prices. Her work with the Northwest Turkey Federation secured a nationwide market for Montana’s premium quality “Norbest” turkeys, making Montana’s turkey industry the most profitable in the nation during the Great Depression.

Cushman inspired many new, young poultry growers and introduced poultry production into Montana’s 4-H clubs. She recognized that poultry-generally overlooked by state 4-H leaders in favor of beef, cattle, and sheep-was a mainstay of home economies and an essential source of income for women. Harriette particularly liked working on Montana’s Indian reservations, where profound poverty and lack of economic opportunity were most persistent and where poultry raising could make a tangible positive impact. She was greatly honored when the Blackfeet, in gratitude, made her an honorary

tribal member.

Harriette worked long hours and logged over ten thousand miles a year, often by train, to meet with poultry growers. She was an avid outdoorswoman and spent her free time camping, hiking and photographing her adventures. For over 30 years, she wrote weekly letters to her parents in New York chronicling her work, her concerns for the environment, and poetry, most often about nature and the landscape.

Through her generosity, she helped found the Montana Institute for the Arts to promote arts throughout the state and she actively supported Montana’s libraries and the development of the McGill Museum, now the Museum of the Rockies.

In 1969, nine years before her death in 1978, Cushman wrote six hundred handwritten invitations to be sent out upon her death. Her invitation began, “I was raised on Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s lines, so many faiths, so many creeds, so many paths that wind and wind, while it’s just the art of being kind that’s all the old world needs.” Harriette passed away on August 10, 1978 and over 100 friends came to the Student Union Building as she requested to have a reception including little cakes and coffee.

She willed her estate to the university, providing funds for both the Indian Center and scholarships for outstanding American Indian students.

Frances Senska was born in 1914 and grew up in Cameroon, where her parents were missionaries. Her mother was a teacher and her father was a woodworker as well as a doctor who taught young Frances how to work with woodworking tools. The people of Batanga, Cameroon also contributed to her deep sense of utilitarian crafts, “Everything that was used there was made by the people for the purposes they were going to use it for. It was low-tech…and they were experts at what they did,” Senska later recalled.

Frances served in the United States Navy from 1942 to 1946 during World War II, where she was trained as a pilot. During her time in the military, while stationed in San Francisco, she took a night course in ceramics and so began a lifelong relationship with clay. After the war, Frances used the GI bill to return to school, initially, at the University of Iowa and then at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan.

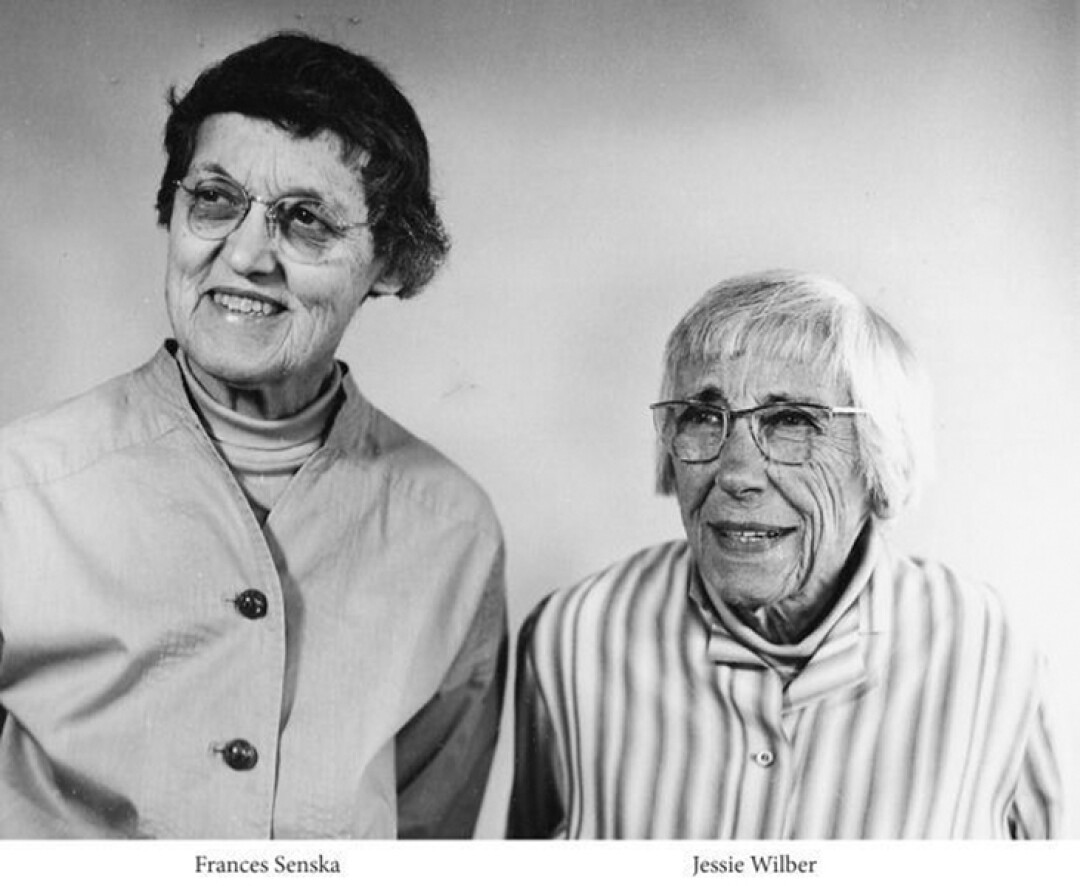

In 1946 Montana State College, now Montana State University, hired Frances Senska to teach ceramics. Senska had a master’s degree in applied art, and had just taken two classes in ceramics, but this hiring proved to be fortuitous for the college and for America’s burgeoning midcentury crafts movement. It was at Montana State that she met printmaker Jessie Wilber, who became her lifelong companion and with whom she helped cultivate Montana’s art community.

Working with architect Hugo Eck, Frances and Jessie Wilber, designed their own house and art studios on Sourdough Road in 1953. They created a conservancy on a portion of their wooded property for trails and a park, and took an active role in the community, being present at many city council meetings.

Unassuming and always a good neighbor, she was also a force to be reckoned with when she felt strongly about an issue. Many admit to being scared to death of her, probably because of her military manner, but she was also referred to as a fairy-godmother and is considered the “grandmother of ceramics in Montana”. Frances was instrumental in the development of The Archie Bray Foundation located in Helena.

Generous with her students, Senska was also generous and involved in her community. An avid supporter of the Swim Center, she and Wilber once spearheaded a fundraising effort to keep the struggling pool open. She was a powerhouse in the Montana Institute of Arts at its inception and supported the community of arts of all kinds.

Senska remained humble and unconcerned with fame. While others admired and collected her works; she held on to only a few of her own pieces, keeping instead work made by her students and a little black pot from her childhood in Cameroon. In her artist’s statement, Senska simply said, “I make pots.” Frances retired from teaching in 1973, but never retired from her art and continued to throw pots into her 90’s.

Frances and Jessie were jointly awarded the Montana Governor’s Award for Distinguished Achievement in the Arts in 1988. Jessie passed away the following year and Frances Senska passed away Christmas Day 2009.

| Tweet |