MSU researchers apply high-tech sensors to improve maple syrup quality

Wednesday Oct. 19th, 2022

BOZEMAN — Maple candies, glazes and the syrup drizzled on a hot stack of pancakes could all get a little sweeter and fresher-tasting thanks to research at Montana State University.

Backed by a new three-year, $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a team led by MSU researcher Stephan Warnat in MSU's Center for Biofilm Engineering is developing innovative sensor networks to monitor microbes that accumulate in equipment used to harvest maple sap and which are known to degrade the taste of finished products.

"What we want to know is, what’s happening with the microbes inside the sap lines, how does that relate to the quality of the sap and then the syrup, and what are the best practices we can recommend for cleaning the lines," said Warnat, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering in MSU’s Norm Asbjornson College of Engineering.

With most syrup being made from sugar maples in eastern Canada and the U.S. Northeast, the Montana researchers may seem unlikely allies of the cause, according to Warnat, but the project is a natural extension of his work to create sensors for measuring microbes in tight, enclosed situations. Originally developed as part of a NASA-funded project to help the space agency study biofilms that form in the plumbing systems of spacecraft, the technology is in many ways ideal for tackling the challenge facing syrup producers, he said.

According to the USDA, maple syrup was a $132 million industry in the U.S. in 2020, with producers making 4.1 million gallons of the sweet liquid. But before syrup can be bottled, sap must be harvested from the trees, with farmers drilling small holes in the trunks and using networks of thin hoses to collect the fluid before boiling it down to concentrate the sugars and unique flavors. Although producers are aware that biofilm buildup can negatively affect syrup flavor, not much is known about the microbes themselves, according to MSU researcher Seth Walk, a co-leader of the new project.

"One thing we know is that microbes love eating sugar,” said Walk, professor in the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology in MSU’s College of Agriculture. “But in this case, we don’t know what they convert it into that can have an off-putting taste and smell."

Walk received a $500,000 USDA grant last September to lead a project focused on sampling microbes from sap lines and using DNA analysis to better understand why biofilms form in some lines but not others. Nicholas Pinkham, an MSU bioinformationist in Walk's lab, is a partner on that project, and both projects include Warnat as well as Christine Foreman, professor of chemical and biological engineering and researcher in the Center for Biolfilm Engineering, and Jesse Randall, a forestry specialist at Michigan State University. The two projects are well aligned to make a positive impact on syrup production, Walk said.

“Right now, with just their limited observations in the field, there’s no way for farmers to know which of their lines have high microbial load and what they should do about it,” Walk said. Farmers typically run disinfectant and water through the lines at the end of the season, but if that proves ineffective, they may have to dispose of expensive but unusable equipment or sell a lower-quality batch of sap at a lower price for making products like candies.

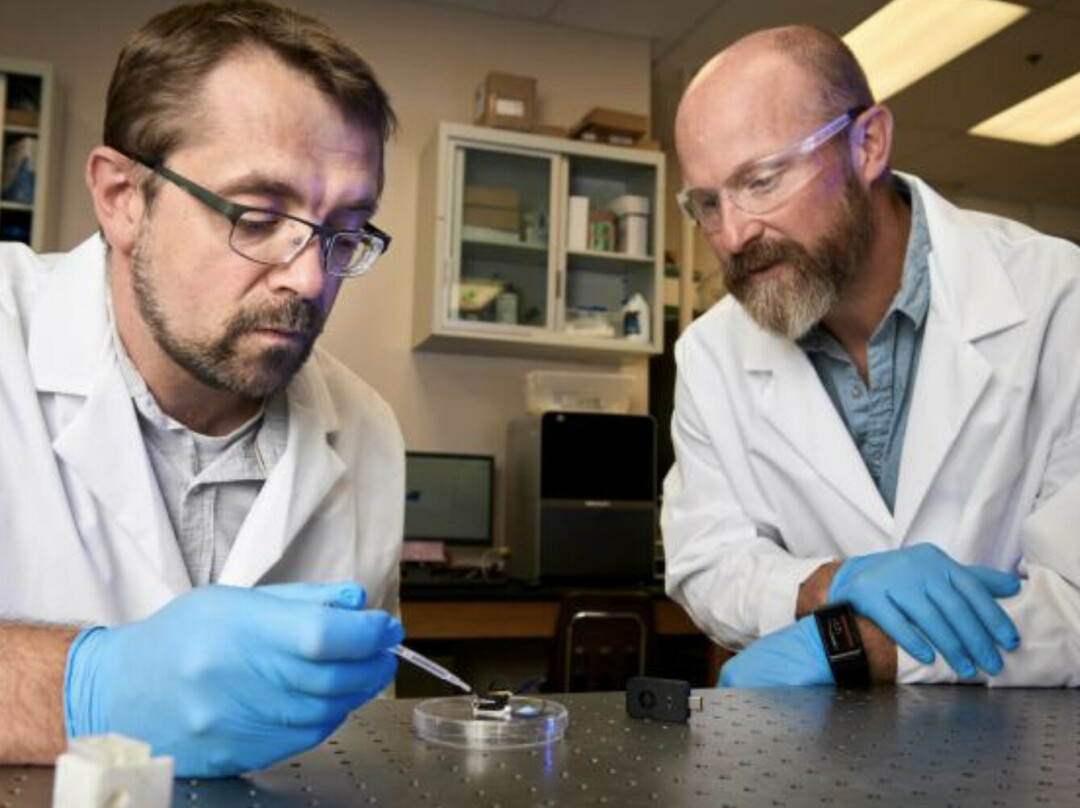

The sensors, developed in Warnat’s lab by mechanical engineering doctoral student Matthew McGlennen, each consist of a small wafer of glass imprinted with very thin lines of gold. When a precise electrical current is passed through the metal, the resulting signal can be used to infer if biofilms are found on the glass surface. Knowing that would provide a wealth of information for tailoring disinfecting protocols, Warnat said.

The focus of the new project is to fine-tune sensors that can both detect the maple microbes and tolerate the temperature swings and other challenges of the sap-line environment as well as link them together so that the information can be displayed on a computer screen. The researchers will also host outreach sessions with maple producers to educate them about the potential for the new technology.

"We think we can get to a point where a farmer sitting in the office can see a readout of the current state of the harvesting lines and know what the protocol is for cleaning them,” Warnat said. The tool could also be used to monitor microbes in municipal water towers, air conditioning ducts and other hard-to-reach places, he added.

"It’s exciting to take these sensors to the field with a new application," Warnat said.

| Tweet |