Bozeman’s Best Friend: History Tails of Local Hounds

Rachel Phillips | Friday Sep. 1st, 2023

Bozeman is, and was, a dog-loving community. For centuries before the town even existed, dogs were essential helpmates and companions to Native people living, hunting, and passing through the Gallatin Valley. More recently, when farms and ranches appeared, dogs again went to work. They faithfully herded and protected livestock and provided companionship to humans, never faltering as “man’s best friend.”

The abundance of domestic dogs in the Gallatin Valley was noted by early newcomers. In the mid-1860s, a small community near what is today Four Corners was briefly known as Dogtown. According to local historian Grace Bates, Dogtown had a saloon, a store, and a blacksmith shop. It was located on Middle Creek, or what is today called Hyalite Creek, likely just north of Monforton School. In her book Gallatin County Places & Things Present & Past, Bates stated the community was named by early resident Catherine Boyle Waterman in 1866, in honor of the large number of dogs present in the area. Dogtown is also mentioned in the 1869 diary of Enoch Douglas Ferguson, who settled on land west of Bozeman. Ferguson recorded at least three visits to Dogtown or “Dog Town” before the end of 1869. In a 1975 oral history interview, local resident Margaret Boylan described how she and her husband George purchased a ranch eight miles west of Bozeman, occupying the site of the former Dogtown. Boylan stated that “they called it Dogtown because everybody there had a lot of dogs.”

While some early settlements like Dogtown disappeared, growing communities like Bozeman soon needed formal regulations to address issues associated with an increase in pets and livestock within city limits. Bozeman was incorporated as a city in 1883, and some of the earliest laws focused on animal control. City Ordinance No. 7, adopted May 1, 1883, provided for the creation of a city pound to house loose domestic animals, including horses, cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. Dogs in particular were addressed in City Ordinance No. 12, adopted on May 10 that year. Every dog owner was required to register their canine with the city marshal and pay a licensing fee of two to four dollars per year. Dogs were required to wear collars with their registration number and owner’s name. A dog pound contained loose animals that could be euthanized if the owners could not be found or if the animal posed a danger to the public.

Bozeman dog license tags came in a variety of shapes and colors. A collection of tags at the Gallatin History Museum includes examples from 1902 through the 1980s. While many are simple metal circles, rectangles, or triangles, some dog tags are shaped like dog’s heads and even fire hydrants. Each Bozeman tag records the year, license number, and the words “Dog Tax.” In addition to being licensed, local dogs were also well-photographed. The Gallatin History Museum photograph collection features dozens of photographs that include four-legged family members. Occasionally, the photographed dogs are named, or featured solo in professional photographs. Dogs named in museum photographs include Duke, Tip, Gyp, Fritzy, Red Sally, Bill, Judy, Ranger, Dusty, Chief, Leader, King, Sandy, Tootie, and Bouncer. Like today’s monikers, nineteenth and twentieth century pup names ran the gamut from traditional to one-of-a-kind.

Perhaps Bozeman’s most famous dog was Bruno, sometimes referred to as a mixed-breed, sometimes as a staghound. In 1924, a young dog appeared at the Northern Pacific Railroad yards on the northeast side of Bozeman. Nobody seemed to know where the dog came from, but workers assumed the puppy had fled sheep-ranching duties. Initially, railroad workers tried to scare away the animal but were unsuccessful. Attitudes toward the dog rapidly changed and the canine was named Bruno.

Interestingly, Bruno seemed indifferent to humans but became quickly and firmly attached to a couple of the locomotives. Ron Nixon, a retired railroad worker who spent three years in Bozeman with Bruno, explained the situation in an article titled “Class L-6 (900-919)” for the Northern Pacific Motive Power. “Soon the switch crew accepted him as one of their own—fed him and watched over him regardless of the fact that he only tolerated them—putting forth all his affection on the L-6 switcher.”

According to several sources, Bruno slept in Bozeman’s Northern Pacific Roundhouse next to switch engine No. 911 and spent his days accompanying the locomotive wherever it traveled, following its back-and-forth motions precisely. Nixon claimed that “Bruno would have absolutely nothing to do with any locomotive except the L-6 switcher. He totally ignored the giant Z-4 mallets in helper service. He paid no attention to the W and W-3 mikes or any of the passenger or work train engines. He had a most complete disdain for Milwaukee Road switcher, encountered daily on adjacent tracks.” Nixon explained that Bruno in fact “adopted” both No. 911 and No. 914 L-6 engines. When one locomotive was out-of-service for repairs, the dog faithfully watched over the other.

By 1927, Bruno had been given the honorary title of Northern Pacific Switchman. He closely observed his human counterparts and learned their signals and the sounds of the engine by heart. Several sources claim the dog carried a stick, imitating the switchman carrying a “break club.” Bruno was so in tune with the locomotive’s movements that he had a well-worn trail he followed next to the machine over and around obstacles. It was estimated the dog likely traveled close to sixty miles a day.

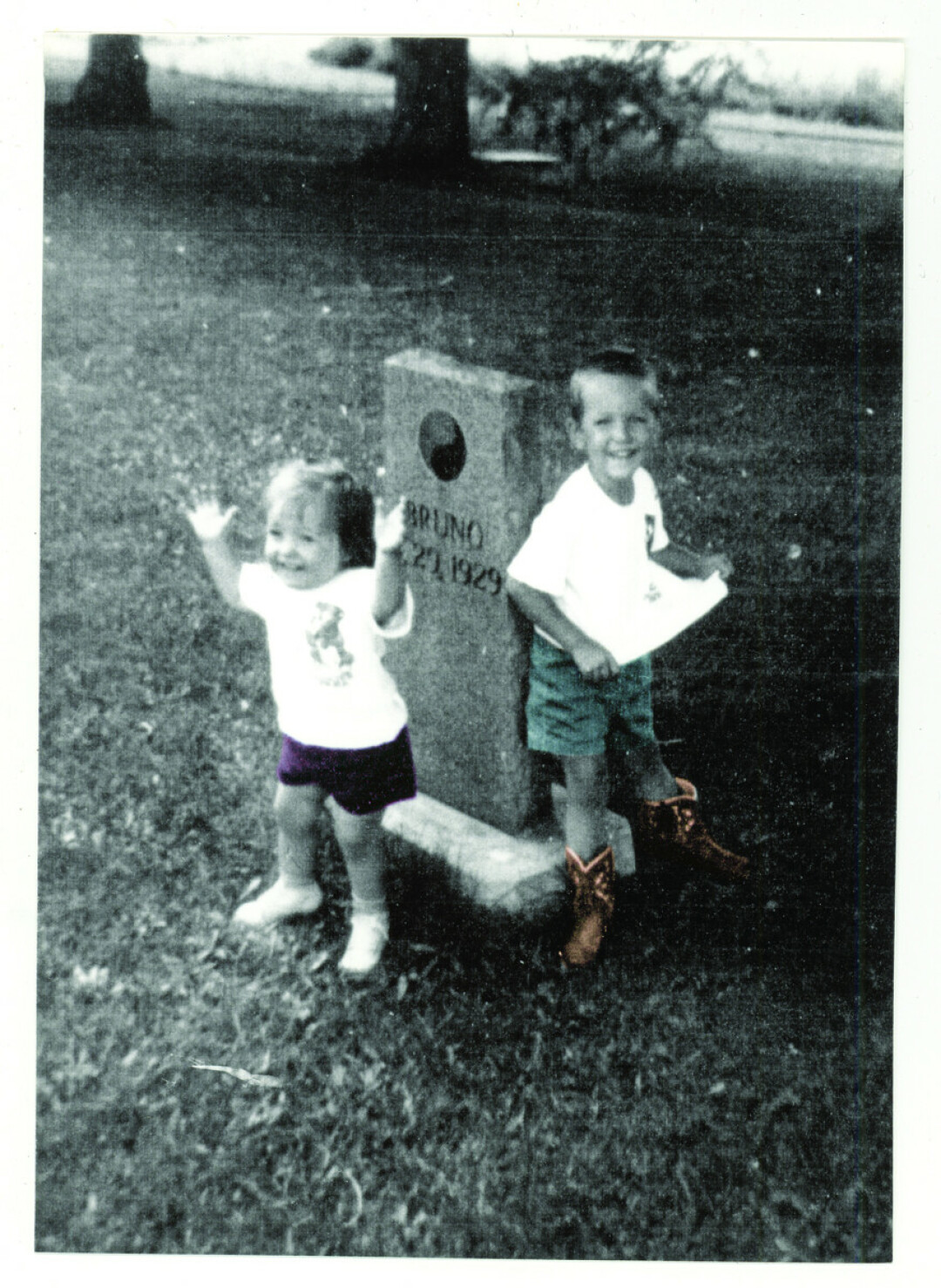

Sadly, on March 29, 1929, tragedy struck. According to Nixon, Bruno’s foot got stuck and he was run over by engine No. 911. Another local railroad historian, Warren McGee, believed that the crew realized they’d forgotten something and changed directions suddenly, accidentally hitting the dog. Whichever the case, railroad workers were heartbroken. Bruno was buried near the roundhouse office at the east of the station. Railroad employees pooled their money and purchased a grave marker for Bruno, simply recording his name, death date, and the Northern Pacific Monad symbol.

News of Bruno’s death spread through the national railroad community, and even Montana state agencies sent their sympathies to the Bozeman railroad workers. On April 10, 1929, a local newspaper quoted: “‘The car samplers of the Montana Grain Inspection Laboratory extend their deepest sympathy to the Northern Pacific switch crew in the loss of their faithful dog. We will miss him whenever we sample a car in the Northern Pacific yards.’”

In the 1980s, railroad historian Warren McGee rescued Bruno’s gravestone and brought it to Livingston, where it still rests today in front of the Yellowstone Gateway Museum, next to Northern Pacific Caboose 1266. Today, dogs like Bruno continue to make our lives brighter. What would we do without our own Dukes, Fritzys and Rangers?

| Tweet |