The Tenacious Women of Bozeman’s Past

Marion Jackman | Wednesday Mar. 1st, 2023

In downtown Bozeman, next to the courthouse stands the Gallatin History Museum, a lovely brick building that preserves the area’s past. In honor of Women’s History Month, I interviewed the amazing women who work there, and asked each of them to name their favorite woman from Gallatin’s history.

Lynn Yeager, Charlotte Mills and Rachel Phillips not only protect Gallatin Valley legacies, but dedicate themselves to answering questions and solving the timeless mysteries left by those long since gone.

Lynn: I am the Museum’s Executive Director. I started here in June of last year. I actually moved here from Detroit. When I hit my 30’s, I decided I wanted to do what I’ve always dreamed of, which is to run a museum. They took a chance on me, I took a chance on them, and here I am. I also grew up on an 18th Century iron plantation in Pennsylvania. So that has been my life since I was six years old, running around wearing a bonnet on the farm, carrying around chickens and giving school tours, so this was the perfect opportunity.

Marion: So, who is your favorite woman in Gallatin Valley history?

LY: This is where Charlotte comes in. She can tell the story better, because it’s one of her ancestors, Granny Yates. I will let her take the lead on that.

Charlotte: I’ve worked here part time for four years as a research assistant. Granny Yates was a pioneer who brought in 13 wagon train loads of people. She arrived in the Gallatin Valley around 1865. She has hundreds and hundreds of relatives still here. Granny was a pretty aggressive and self-made woman. She was independent, hardcore and rough. Her husband died in the Civil War; she had eleven children and three step-children who happened to be her sister’s children. Her husband was first married to her sister and when she died, he married Granny. So, she raised 14 kids.

LY: This woman was a hard working independent, self-made hustler who had faced all these hardships. She lived to her 90s. She died in 1907.

MJ: That’s an impressive lifespan.

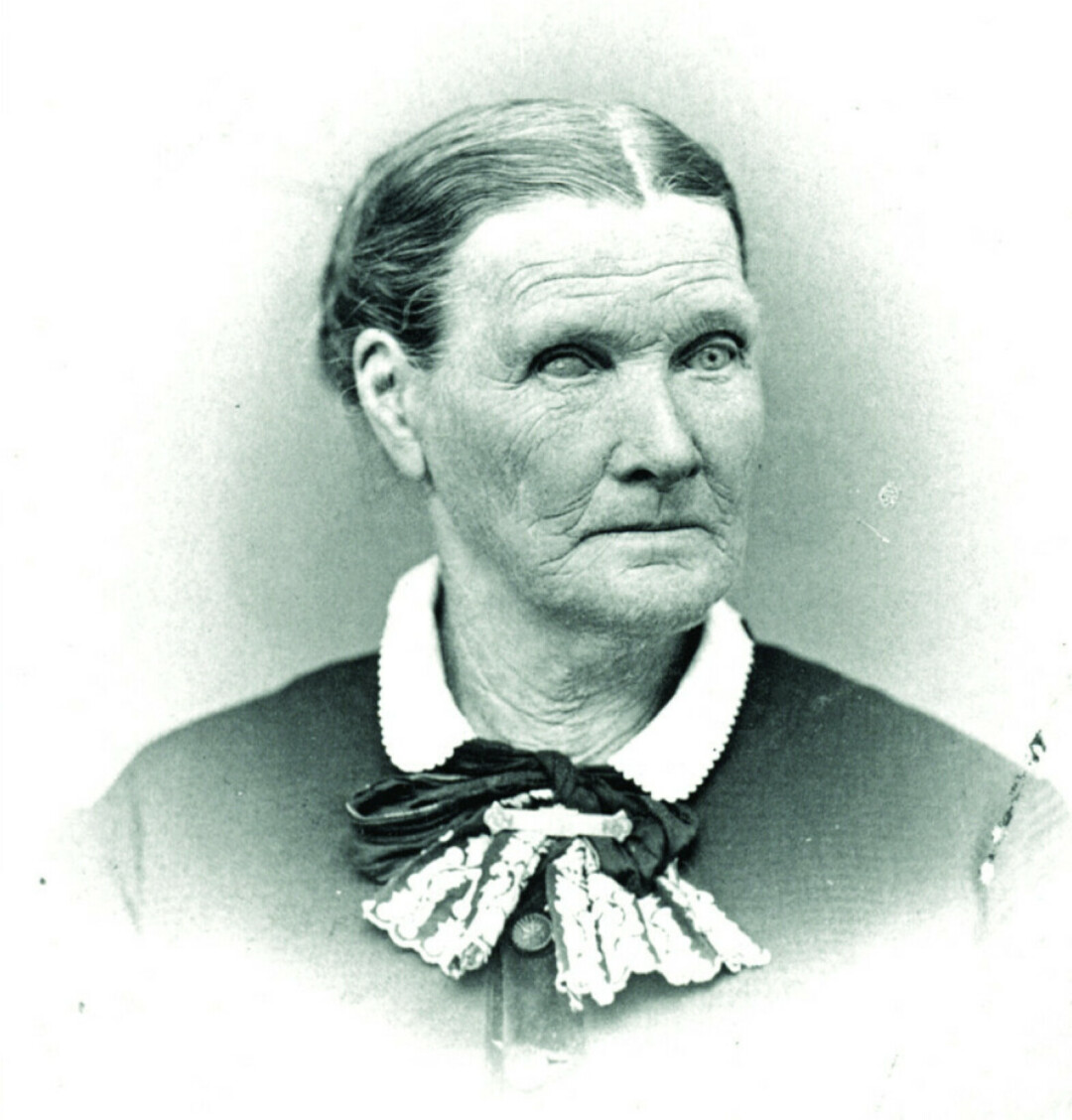

Mary L. Wells “Granny” Yates.

Photograph courtesy of the Gallatin History Museum

LY: Yes. And then you have 14 kids, going through this tough lifestyle. It’s hard being a single mom, but she raised her kids. She made a life. She made a name for herself, which wasn’t easy, especially during that time. So, when Charlotte told me her story and I saw her picture, I was like, that is amazing. That is just inspirational. Even now, with Charlotte and her sister, Mary, it’s interesting because the traits that I saw in Granny, I see in them. They’re hard working women. They know the history. They’re hustlers in their own way. It’s cool to see a woman whose traits can be seen through her lineage, and I love that. That’s why Granny Yates is my favorite.

CM: Her first name is Mary, but everyone calls her Granny. She was actually buried in the Dry Creek cemetery. She was a sturdy, strong minded woman.

LY: You and your sister get that from her! They do. Strong Montanan women. That was my greatest example coming here. When she told me about Granny Yates, I thought, that sums up every Montana woman I’ve met.

MJ: She raised 14 children by herself?

CM: Well, she didn’t bring all 14 across the plains. The two older ones stayed in Missouri.

MJ: That’s a lot of distance to travel in a covered wagon. Was she a homesteader?

CM: I can’t exactly tell you where she homesteaded, but all her children were homesteaders. I think a lot of the time she lived with her children. She actually settled in Virginia City, but she migrated out this way, and her children went with her. She had this cane and she was mean. My dad was born in the early 1900s. He was seven years old when she died. He actually lived with my grandmother, and it was his job to take her out to the outhouse. He was always hit with that cane so he thought, ‘Someday I’m going to get even with her.’ And one day when he led her out, he ran her straight into the clothesline.

MJ: That’s one way to get even! Did she ever remarry?

CM: No, she never did.

MJ: How did she make a living?

CM: When she was in Virginia City, she made apple pies and sold them for an atrocious amount of money. I want to say they were five dollars? When they came here, everyone was involved in farming. Her daughter Annie, my great grandmother, carried on that tradition. There’s a story about the painted Belgrade bull next to the Chamber of Commerce building in Belgrade. That was her bull. I think it’s pretty amazing she lived as long as she did, even with such a rough life. She was very vocal, very opinionated, tenacious. She had a ton of perseverance.

LY: In fact, for a lot of women, life was not easy. It was not a cake walk. A lot of times women were left on their own, and they made something of themselves. That’s trickled down though their family. So to see that, it’s something.

CM: When you stop and realize that in order to eat you had to raise your own beef, grow your garden, milk your cows and live in a house with a dirt floor… it was a hard life. And on the frontier, where many women died in childbirth, she had ten children who lived into adulthood. At one time, it was determined she had over a thousand descendants.

LY: So one woman, from Missouri, populated Montana. Her legacy is living on this day.

MJ: Rachel, how long have you worked here?

Rachel: I am the Research Coordinator of the Museum. I’ve worked here maybe 14 years? I lose track of the time.

MJ: What got you interested in the Museum?

RP: Well, I grew up in the area and went to MSU, majoring in history, minoring in museum studies. I started to volunteer here while in college, which turned into an internship. Then, after college, after a year of working at the post office, the executive director of that time contracted me and said the department needed help digitizing and cataloging the records here, which brought me back.

MJ: And who is your favorite historical figure?

RP: Charlotte is pretty involved in my favorite person, too. My favorite person is Sammy Williams, and she is quite interesting. We are still finding out more about her. Sammy Williams was a cook at a ranch in Manhattan. She actually came here in the early 1890s, I think. We are not actually sure on the year.

CM: She was registered to vote in 1896, so she had to be here early 1890s.

RP: The funny thing about her is that no one knew she was a woman until her death.

MJ: Oh, wow!

LY: Right?

CM: She died in 1908, I believe.

RP: She showed up here dressed as a man. She cooked at a few different ranches around Manhattan until her health began to decline. According to the story, one day she didn’t show up to make breakfast for the farm hands, and they found her dead in her bed. Of course, the undertaker found out she wasn’t a man! No one knew who she was, so she was buried at the cemetery in Manhattan. Not knowing her name, the townspeople, (she had a lot of friends) chipped in and purchased a headstone that read, “A female whose real name is unknown, but has been for many years Sammy Williams.”

CM: We did find out her real name, though.

RP: After her death, a man in Manhattan thought he knew her family, or where she came from in Wisconsin. I’m not sure how, but he wrote back there, and was able to get a bit of information. Her name was Ingeborge Wekens. Her family was from Norway and had come to northeastern Iowa in the mid-1800s. According to the story, she had been engaged, and the fiancé’s mother decided against the marriage. So Ingeborge, or Sammy, decided to disappear. She started dressing like a man and working as a cook in lumber camps in the Midwest before eventually making her way West.

CM: One of the things I thought was so cool was that she actually was registered to vote, and voted. This was when women were not allowed to vote. She also owned about 328 acres of land. That’s pretty exciting, I think.

MJ: Did any of her family come forward to claim her body?

RP: Nope. She’s still buried in Manhattan.

CM: She left her family behind and started a new life. We also found a story in one of the papers that she’d owned some land back in Iowa but didn’t wait to sell it, and used a false name. So she deeded it to a friend for a dollar; that friend sold it and gave her the money. She seemed like she was a smart person, especially for going undetected for so long.

Sammy Williams was registered to vote in 1894, 1896, and 1900, over 14 years before women received equal suffrage in Montana. Both she and Granny Yates didn’t allow their position, gender or hardship to dictate their lives. They were strong, independent and tenacious—a trait that is continued in Montanan women today.

Women didn’t receive equal suffrage in Montana until 1914.

Sammy Williams’ gravestone: Sammy Williams’ gravestone in Meadowview Cemetery near Manhattan, Montana. Photograph by Rachel Phillips.

894 Voter Registration: An entry for Sammy Williams in the 1894 Gallatin County voter registration ledger book in the Gallatin History Museum Archives. Sammy was registered to vote in 1894, 1896, and 1900.

| Tweet |