Montana History with a Modern Twist

Clubfoot George

Pat Hill | Monday Oct. 2nd, 2017

Clubfoot George met his fate at the end of a Vigilante Association’s hangman’s noose in Virginia City over 150 years ago, and last June, nearly 50 members of his family gathered in that old Montana mining town to remember their ancestor and take part in a somewhat curious yet memorable ceremony at his gravesite.

George Lane was also known as “Clubfoot George” because of his deformed foot. Interestingly, it was this foot that led to the family gathering at the very site on a hill overlooking Virginia City where Clubfoot George and four others were buried after being hung in January of 1864.

Other than records like California census reports from the 1850s, there is little specific information regarding Clubfoot George. From those census figures, it appears that George Lane originally hailed from Massachusetts, and the California Gold Rush brought him west in the early 1850s. He did not join in the toil of mining for gold, according to census records, instead choosing to work first on a farm in Yuba County, and later as a store clerk in Calaveras County. But George Lane seemed to follow the scent of gold, and the discovery of gold in Washington Territory drew him away from California and into present-day Idaho in 1860.

It was in Idaho that Clubfoot George first garnered accusations of being an outlaw of sorts, more specifically as a horse thief. Between 1862-’63, Lane was accused of stealing horses in the territory at least twice, allegedly once turning himself in to military authorities at Fort Lapwai to avoid potentially much harsher penalties at the hands of local law enforcement or vigilante types. Lane apparently moved on to Virginia City rather quickly in the fall of 1863 with accusations of another horse theft nipping at his heels.

In Virginia City, then a newly-booming placer mining gold town, Lane went to work at Dance and Stuart’s store, where he reportedly earned a reputation as a good hand with leather, making boots and repairing harnesses. But the timing of his arrival in Virginia City, coupled with the company he allegedly kept, was probably not in his best interests: By late December of that year, the Vigilance Committee of Alder Gulch was formed.

That committee, modeled on a similar organization which had formed in California during the initial lawless years in the gold camps, came together in the wake of several robberies and murders in the Virginia City area and beyond. Clubfoot George was taken into custody soon after the organization of the vigilantes, accused of being a member of the gang who supposedly referred to themselves as “The Innocents,” a gang allegedly led by the sheriff of Bannack named Henry Plummer. In the first six weeks of 1864, the vigilantes tried and hanged over 20 alleged members of the gang, including Plummer and Clubfoot George.

Lane was accused of traveling to Bannack and warning Plummer of the vigilante activity in Virginia City. He was also accused of spying for the outfit, and being an accomplice to murder and robbery. But Clubfoot George reportedly steadfastly denied these charges, and, according to records, told his accusers that “If you hang me, you will hang an innocent man.” But his pleas came to naught on January 14, 1864; though his employer Mr. Dance acknowledged that Lane was a hard worker, he also admitted that he had no knowledge of his other activities. Lane then asked if Dance would pray with him, to which Dance replied, “Willingly, George, most willingly.”

Lane was then led to the makeshift gallows at the site of a partially constructed building, where the nooses were hung from an overhead beam, with wooden boxes placed beneath each noose. Standing atop the box with the noose around his neck, George spied a friend in the gathered crowd, shouted out, “Goodbye, old fellow, I’m gone,” and then leaped from the box without further adieu. A witness reportedly said that “[Lane] was perfectly cool and collected...[he] evidently thought no more of hanging than the ordinary man would of eating his breakfast.”

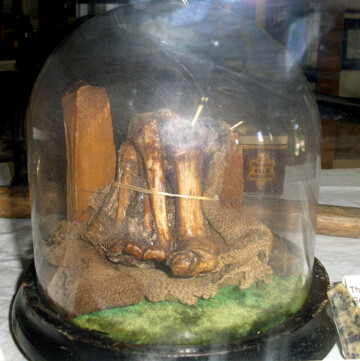

Lane was buried atop “Boot Hill” with four other alleged members of the Innocents who were hung that day, all being placed in unidentified graves. But that wasn’t the end of the story. Though the dates and participants vary depending on which account is read, it appears that by 1907 some folks in Virginia City were quite curious as to the exact location of the men placed in those five unmarked graves in 1864. A former member of the vigilante association said he knew which body was where, and after pointing out Clubfoot George’s grave, his body was dug up, and his petrified club foot was removed and put on display in a glass case in various Virginia City locations.

George’s foot remained on display for well over a century after being removed from the body. It became an object of fascination among tourists to the old gold town, which has retained much of its 19th-Century originality. But members of the extended Lane family, of which there are many in Southwest Montana, decided a few years back that it was time for George’s foot to cease being a tourist attraction, and instead rejoin the body it was removed from. Virginia City was reluctant to give up one of its more grisly tourist mainstays, however, but the family came to an agreement with the town thanks to the miracle of modern technology. A 3-D mold of Clubfoot George’s foot, exact in every detail, was given to Virginia City historians in exchange for the petrified foot.

George’s foot was then cremated by the family, who gathered on Boot Hill on June 24 for a ceremony to essentially rejoin the foot with the body.

“Well, there’s not much left of George’s foot,” family member and Catholic Church Deacon Robert Lane told the crowd assembled for the ceremony. But as preparations were made to sprinkle the ashes of the foot onto the grave, it seemed that George was going to remain stubborn to the end. Family members struggled to open the box holding their ancestor’s ashes, but they finally got the vessel open. After first sprinkling holy water from Ireland upon the site, Deacon Lane scattered the ashes of George’s foot upon the top of his grave, and Clubfoot George got his foot back after having it separated from his body for over 100 years.

Family members then recounted tales of their ancestor, and a trio of musicians also paid homage to the man that many members of Virginia City in January of 1863 thought was innocent of the charges brought against him. A member of MontanaPBS’s “Backroads of Montana” crew was even on hand to capture the ceremony on video, which means many more people in the Treasure State will eventually be able to witness the event on television.

“I thought it was a fitting end to a long nefarious part of our family history,” said John Keenan, whose mother’s grandmother was a Lane. “It was the right thing to do.”

Clubfoot George Lane’s grave lies just north of the main drag through Virginia City, and the 3-D mold of the alleged road agent’s foot can be seen at the Thompson-Hickman Museum at 217 Idaho Street.

| Tweet |