Legendary Locals of Bozeman: Spooky Tales

Rachel Phillips | Saturday Oct. 1st, 2016

From its inception as a supply town during Montana’s gold rush in the 1860s, Bozeman has attracted visionaries, leaders, and pioneering thinkers. Now one of Montana’s fastest growing cities, Bozeman still retains elements of the past while looking to the future. Streets named Alderson, Rouse, and Willson pay homage to early founders, while new start-up companies coexist with 100-year-old businesses. Educators and pioneering thinkers stimulate new ways of thinking, and artists, musicians, and entertainers add to the local culture. Sports legends and outdoor athletes continue to amaze, and inspiration emanates from extraordinary individuals. In honor of Halloween, here are several of the more spooky excerpts from the book Legendary Locals of Bozeman, the newly released title by Rachel Phillips, Research Coordinator at the Gallatin History Museum.

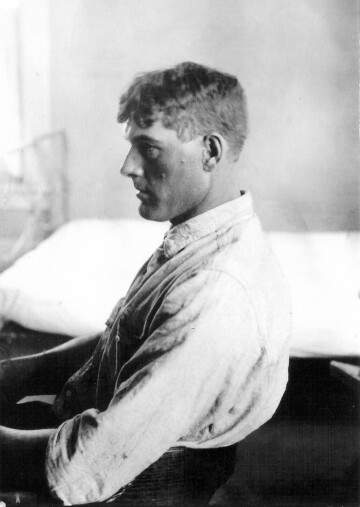

Seth Danner

On July 18, 1924, Seth Orin Danner was executed by hanging in the Gallatin County Jail after being convicted of the 1920 murders of John and Florence Sprouse. Seth’s wife, Eva, exposed the crime to a sheriff’s deputy in 1923, perhaps spurred on by the couple’s deteriorating relationship. As Eva explained, the two couples were camping together along the Gallatin River that summer, trapping and hunting. One evening, the two men left the campsite to tend to their traps, and only Seth returned. Eva claimed that Seth killed John, then murdered Florence Sprouse with a hatchet after she repeatedly questioned him about John’s whereabouts. Throughout his trial, Seth admitted to bootlegging and the occasional robbery, but was emphatic that he was no murderer. Seth Danner suggested that Florence Sprouse’s violent ex-husband was to blame, but was convicted nonetheless.

William and Mary Blackmore

Wealthy English couple William and Mary Blackmore stopped in Bozeman in 1872, intending to take a brief rest before exploring Yellowstone. However, Mary became suddenly ill, and Lester and Emma Weeks Willson welcomed the couple into their home. Sadly, Mary died only days after her arrival. William Blackmore purchased several acres of land on a hill overlooking town, buried his wife, and donated the land to the city. One can still find Mary’s pyramid-shaped gravestone in what is now Sunset Hill Cemetery. Her marker mimics the form of Mount Blackmore in the Gallatin Range, named in her honor by Dr. Ferdinand Hayden, Yellowstone explorer and recipient of financial backing from William Blackmore. As for William, he returned to England, where his empire crumbled and his life ended tragically in suicide.

Big Horn Gun

Much of the history of the Big Horn Gun is unknown; but, nonetheless, the cannon played an important part in Bozeman’s military and social history. Likely cast in Europe in the later part of the 18th century, the weapon’s arrival in Bozeman dates to 1870, when Henry Comstock and his group of down-on-their-luck Wyoming gold miners halted their wanderings in Bozeman, leaving the gun with local mill owner Perry McAdow.

Four years later, after restoration by local gunsmith Walter Cooper, the Big Horn Gun accompanied the Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition on a journey into eastern Montana. During preparations for the trip, it was discovered that oyster cans from Lester Willson’s store fit the gun’s barrel perfectly. Expedition members were all too glad to assist in removing the original contents of cases of donated oyster cans, after which the containers were filled with shrapnel. In his reminiscences, guide Jack Bean remembers the gun’s distinctive sound during firing—“where is yee—where is yee—where is yee”—as the contents of the tin cans went in every direction.

After the 1874 expedition, the Big Horn Gun led a somewhat quieter existence, only being fired off on special occasions, such as the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883. The icon eventually came to rest in front of the Gallatin County Courthouse on West Main Street, where locals used it for photograph opportunities. The gun’s most recent firing occurred in the middle of the night on March 20, 1957, when an unknown group loaded it up and lit a fuse, waking the sheriff and breaking windows in the courthouse and the Gallatin County High School across the street. The culprits never came forward, but as a preventative measure against future disruption, the cannon’s barrel was filled with concrete. The Big Horn Gun was removed from the courthouse lawn in 1994, restored, and given a new wheeled carriage before being put to rest in the Pioneer Museum (now the Gallatin History Museum), where visitors can safely enjoy it.

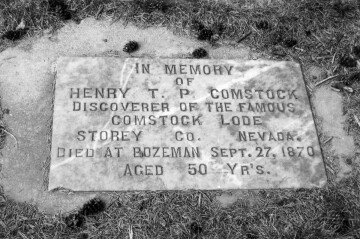

Henry Comstock

September 27, 1870 marked the suicide of one of Bozeman’s most nationally renowned (if not one of its briefest-residing) citizens. Nevada silver miner Henry Comstock, or “Old Pancake,” managed to cement his name in American history before his life ended tragically in Bozeman. After selling his share of the Comstock Lode in Virginia City, Nevada, the ambitious miner traveled north hoping to strike it rich but never meeting with success. He joined a group of prospectors in Wyoming; they finally ended their unsuccessful search after arriving in Bozeman, where the group’s members parted ways. Comstock, who by that time was broke, homeless, and disliked by virtually everyone, lived out the rest of his days alone in a hovel on Main Street before ending his own life.

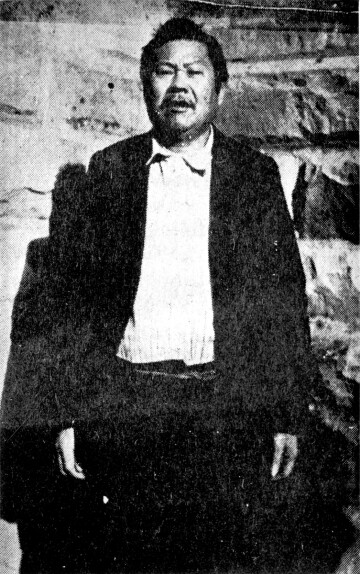

Lu Sing

Lu Sing’s history represents some of the darker aspects of Bozeman’s early years. On October 3, 1905, a Chinese immigrant named Tom Sing was killed with a hatchet in a local restaurant. Lu Sing (unrelated to the victim) was arrested for the crime, but his motive was fuzzy. Theories ranged from a murder-for-hire plot to a crime of passion involving Tom Sing’s wife. Lu Sing’s defense attorney argued that other members of the Chinese community forced him to commit the act on pain of death. All arguments failed, and the prisoner was sentenced to hang. Lu Sing was executed in the wee hours of the morning on April 20, 1906. Disturbingly, the execution did not progress as smoothly as it should have, and it was not until 15 minutes after the platform dropped that Lu Sing was pronounced dead. As the newspapers described, this was more of a “strangulation” than a “clean hanging.”

| Tweet |