Historic District Spotlight:

Topography and the Evolution of Bozeman’s Sewerage, Part I

Courtney Kramer | Sunday Feb. 1st, 2015

Of the many tax payer funded public works projects built by the City of Bozeman, none is more integral to protecting the public’s health, safety and welfare than the sanitary sewer system. As growth continues to the west, the Public Works Department is challenged with moving new sewerage uphill to the treatment plant on Springhill Road. Since 1901, Bozeman has utilized natural topography and technological advances to deal with the City’s waste. The City’s cyclical investment in sewerage infrastructure is a tangible reminder of the value our predecessors placed on preservation of the community’s health and environment.

Bozeman was founded in the middle of the nineteenth century, an era rife with reports of disease epidemics. Some, like diphtheria, whooping cough and tuberculosis, are illnesses spread by exposure to infected patients. Others, like cholera and typhoid, are bacterial infections transmitted through consumption of water contaminated with fecal matter from an infected person. Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal infection which has an incubation period (time it takes from one bacteria to multiply into many) of two hours to five days. Groundwater can move cholera bacteria from cesspools to water sources like communal wells, where the disease’s bacteria multiply and affect an exponential number of people. In an era before intravenous hydration, patients died of an electrolyte imbalanced caused by dehydration.

Sanborn Maps reveal the use of outhouses and “water closets” in Bozeman. The Guy House Hotel, located on the north east corner of East Main Street and North Black Avenue, had a two story “water closet” located at the north end of the building along the alley. Given the lack of infrastructure, this facility probably included a basement cesspit which was routinely cleaned out and dumped into Bozeman Creek.

The topography of the eastern Gallatin Valley played a crucial role in the development of Bozeman’s sewerage. Consulting civil engineers have described the natural terrain as “a series of long, narrow parallel drainage courses that drain from the South to the North.”

Almost imperceptible when travelling by car, the South-to-North slope allowed early 20th century engineers to utilize gravity to move material from private residences to a centralized outfall location. Bozeman’s modern sewerage now drops almost 60 feet of elevation per mile. The high point at Goldenstein Road (elevation 5,050 feet above sea level) drops 385 feet to the treatment plant on Springhill Road (elevation 4,665 feet), a distance of 6.3 miles.

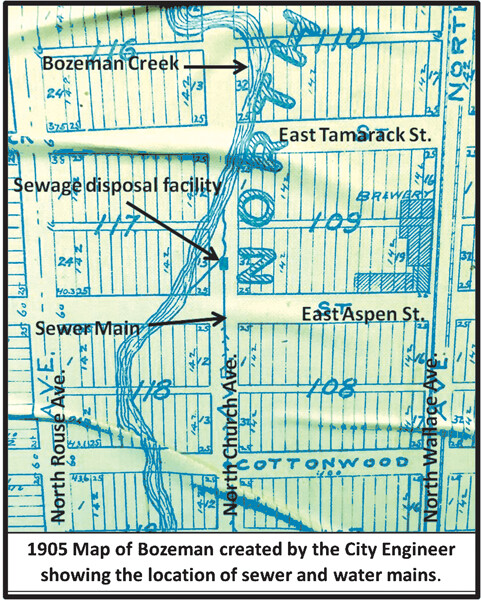

The City of Bozeman moved to develop a public sewerage in the late 1890’s. City Engineer C. M. Thorpe contracted with civil engineer and Park County surveyor S. H. Crooks in late 1900 to create a comprehensive sewerage plan for the City. In March 1901, Crooks presented the City Council with a plan that called for eleven sewer districts and taxation of property owners along the line to pay for the project on a per linear foot basis. The proposed lines followed topography downhill to a single outlet into Bozeman Creek at the extreme north of Church Avenue, north of the East Aspen Street right of way and west of the Lehrkind Brewery.

The Engineering Record, a trade journal for engineers and building contractors who bid on heavy civil engineering projects, reported in June 1901 that, “The Council has approved plans for a sewerage system, prepared by S. H. Crooks, of Livingston, Mont.” The notice appeared as one of 50 notices of communities approving construction of sewers all over the country.

Construction began at a rapid clip. The City passed 52 ordinances pertaining to sewer infrastructure between 1900 and 1910, and eventually created 34 sewer districts by the end of 1910. In an April 1907 report from Thorpe to the City Council, Thorpe reported the construction of nearly six miles of sewer pipe in the City the previous year.

In the same report, Thorpe prioritized installation of new sewer lines by writing, “I believe the most important work and the work which should receive the first attention of the new Council is the construction of the main sewer on the west and north sides of town, which will allow the College to connect and will abate the nuisance of the small brook in the west portion of the City, which at present is an open sewer, and without doubt has caused much sickness in that part of the city. This would also provide a sewer for all of the City not reached by the present system and will extend the present outlet to the East Gallatin River.”

There were other problems with Crooks’ system. A 1905 map created by the City Engineer’s office indicates that a channel from Bozeman Creek diverted water past the sewerage outlet on North Church Avenue and East Aspen Street, which then flowed back into Bozeman Creek. Bozeman Creek water to flush the outlet, however, was a scarce commodity.

Mayor Charles Manry wrote the State Board of Health in August 1907, requesting, “…permission to discharge the sewage from the City Sewer System into the East Gallatin River at a point on the City Dump Grounds… The present sewer discharges into Bozeman Creek at a point near the Northern Pacific Passenger Station and has become a nuisance, owning to the fact that all of the flow of this creek is diverted at a point south of the City for power purposes leaving only the flow of the sewer to carry away the sewage. It is proposed to take in this present sewer and… convey it to the East Gallatin River below the confluence of Bridger, Rocky and Bozeman Creeks. For several miles below the proposed outlet this stream flows through thick brush land, the water being used only for irrigation and stock.”

The Board of Health declined the City’s request and instructed that, “the raw sewage couldn’t be discharged into the river in such volumes to so pollute the stream as to become hazardous to the health and welfare of residents in the immediate area and the entire state.” The Board of health recommended the use of a septic tank sized to accommodate a population of 7,500 people. The 1900 census recorded Bozeman’s population as 3,419; the town finally grew to 7,500 people between 1930 and 1940.

Despite the directive from the State Board of Health, the City struggled to find a long-term solution for the treatment of sewage at the outlet point. The town continued to grow, especially to the west in the Park and West Park Additions, which now constitutes much of the Cooper Park Historic District. The need to expand and improve the system was apparent by 1916, when the Progressive Era City Council put forward a massive public works bond issue that requested over $300,000 in public funding for improvements to the water, storm sewer and sanitary sewer systems.

Opinions on the bond issue were divided. Opponents, including Nelson Story Sr., published an advertisement in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle the week before the election, writing: “So far as the sewerage bonds are concerned, do you want any further large sums of money wasted in sewerage expenditures, a fine worthless example of which we have in a system which the largest taxpayers opposed at the time of installation, and who demanded that sewerage pipes of sufficient size should be used instead of the small, inadequate pipes which were laid?”

City Engineer Carl Widener responded the next day with an editorial. “The two present outlets to our sewer system are creating nuisances in their present positions,” wrote Widener. “This office has repeatedly, in the past three years, had to tell the state Board of Health that the City was getting ready to take these outlets to the river in order to keep them from issuing final orders to us.” Widener also noted that “the west end of the City has never had sewer service, though the property owners have paid taxes to help pay for sewer construction elsewhere.”

City Council members encouraged passage of the bond by publishing a ten-point letter on the bond issue in the Chronicle the Sunday before the election. Point seven described the need to expand the sewage pipes, “With sewage backing up into the basements; with sewers continually congested; with the present outlets of the sewers situated within the city limits and the sewage deposited practically in the city, we are in constant danger of having an epidemic of disease.” The letter underscores the contentious nature of the issue, as it is signed by City Council member Nelson Story Jr., whose father publicly opposed passage of the bond.

The election was held April 3, 1916, and the next day the Bozeman Daily Chronicle reported the bond’s passage by 67 percent of the voters. “The passage of the sewer bonds means that the city will use the $70,000 to install sanitary sewers in the west side of the city and provide outlets and storm and sanitary north of Main Street, emptying into Bozeman creek for the purpose of protecting the north side against the drainage from the rest of the city.”

Construction of the revised system began in 1917. The revised system shifted the outfall line to North Rouse Avenue and carried the sewage another three quarters of a mile north to the confluence of the East Gallatin River, where Griffin Drive meets Bridger Canyon road. Here, the City deferred to the state Board of Health and constructed a primary treatment plant. The facility included two lagoons to separate solids from liquids and filtered the outfall through a series of settling ponds before draining effluent into the East Gallatin River.

The first phase of Bozeman’s sanitary sewer development ended In September 1917, when the City compelled property owners to connect to available sewer lines within one year of the line’s completion or face a $10 fine. The same ordinance prohibited the construction of new privies or cesspools in the City Limits, in order to protect the public’s health.

Next month’s article will examine the roles that federal and state legislation, combined with new technology and the preference to use topography to move waste using gravity, played in improving and then ultimately relocating Bozeman’s sewage treatment plant.

| Tweet |