MSU evolutionary biologist co-authors paper on live birth in an ancient reptile

Wednesday Feb. 15th, 2017

A Montana State University scientist was involved in a recent discovery of a 250-million-year-old fossil from China that has scientists rethinking how reproduction evolved in a group of animals that includes birds, crocodiles and turtles.

The fossil, called Dinocephalosaurus, is a long-necked, fish-eating marine reptile dating to the Middle Triassic period, and contains an embryo inside its abdomen. This unexpected evidence is the only known example of live birth in this large group of vertebrates known as Archosauromorpha.

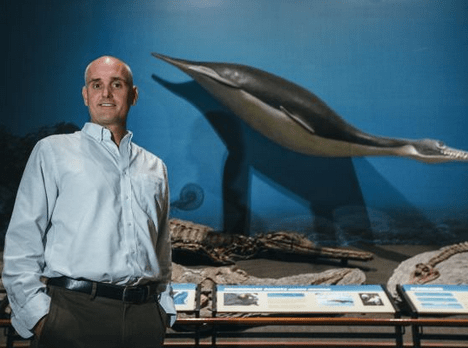

“This is the first archosauromorph species known to have given live birth, meaning it didn’t lay eggs” said evolutionary biologist Chris Organ, an assistant research professor in the MSU Department of Earth Sciences in the College of Letters and Science. “The ancestors of Dinocephalosaurus lived on land — live birth was likely an adaptation that helped it reinvade the marine environment.”

The findings were published Feb. 14 in the scientific journal Nature Communications. Jun Liu from Hefei University of Technology in China, was lead author of the paper, “Live birth in an archosauromorph reptile,” which included Organ, as well as collaborators from England, Australia and the U.S.

The discovery will also be shared in the journals Nature, Science and Science News, among other outlets.

The specimen was found in three limestone blocks in a field in Luoping County, Yunnan, China.

“We were so excited when we first saw this specimen several years ago,” Liu said. “We first saw the blocks lying at the side of a field. We had to remove the soil and dig out the slabs to take them back to the lab for preparation.”

While the discovery shifts the understanding of how reproduction evolved in animals, Organ and his colleagues predicted as much in a 2009 paper published in the journal Nature, “Genotypic sex determination enabled adaptive radiations of extinct marine reptiles.”

“We predicted that if we found a new reptile fossil completely adapted to life in the ocean, it would also have given live birth and have had sex chromosomes,” Organ said.

Dinocephalosaurus sits on the evolutionary timeline between crocodiles and turtles, Organ said, and its ancestors lived on land.

“Like whales and dolphins, it evolved adaptations to live permanently in water without returning to land to lay eggs,” he said. “Whereas sea turtles are reproductively bound to land to lay their eggs, Dinocephalosaurus was free of this constraint by giving live birth, a trait that was likely preceded by the evolution of sex chromosomes.”

This past year, Organ was also one of three authors of a paper that linked bony cranial ornamentation to dinosaur body size. That paper, "Bony cranial ornamentation linked to rapid evolution of gigantic theropod dinosaurs,” was published in Nature Communications on Sept. 27.

| Tweet |