Galloping in the Gallatin

Sunday Sep. 1st, 2019

Gallatin County first organized horse races in the 1870s. In November 1871, the Bozeman Avant-Courier announced four days of racing. By 1878, the Eastern Montana Agricultural and Mechanical Association purchased land, possibly the site of the present-day fairgrounds, and laid out a track. Records through the end of the 19th century are spotty, but Bozeman definitely held race meets between 1884 and 1894 and was part of a state racing circuit from 1901 through 1908. There is no clear evidence of organized horse races between 1909 and 1922. The 1926 Gallatin County Fair—with horse racing—promoted itself as the “Fourth Annual.” It sponsored trotting, pacing, and running races for modest “jackpot” purses. Renamed the “Inter-mountain Fair” in 1927, organizers added relay races as well as a “boys and girls pony race.”

In those years, Bozeman staked its first major claim to American racing history: William “Smokey” Saunders, the jockey who rode Omaha to the Triple Crown in 1935, was born in Bozeman in 1915. Saunders moved to Calgary when he was eight. He exercised horses on Canadian tracks, but returned to Bozeman to live with his uncle, Guy Saunders, and attend high school. He also rode “half-milers” on Montana’s “kerosene circuit”—the smallest meets. In 1932, Saunders went to work for a California-based racehorse trainer, then headed east, where he was tapped by the famed trainer “Sunny Jim” Fitzsimmons to ride Omaha for the Belair Stud.

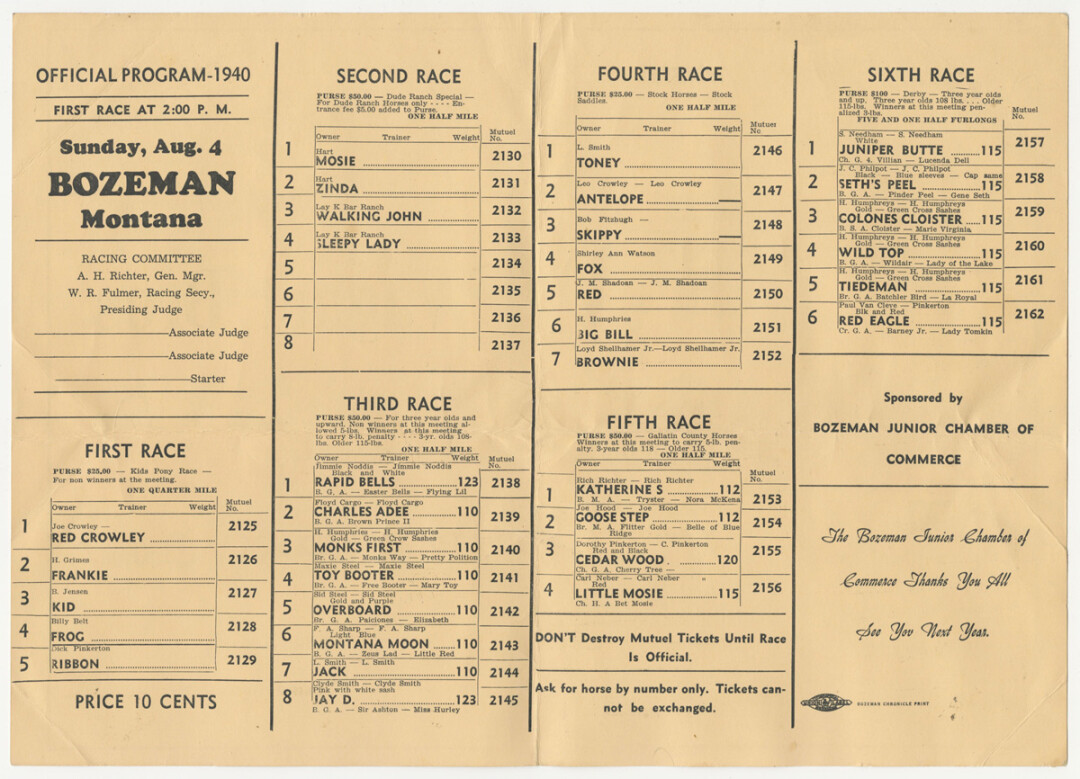

Back in Montana, racing glamour was on the distant horizon for another local boy. Lloyd Shelhamer, Jr. (1923–2010), raised near Wilsall, was said to have so loved his first pair of cowboy boots that he slept in them. He began breaking horses for his father, and the family sold these horses to the military for use as remounts. At the Gallatin County Fair in August 1940, Bozeman’s race meet offered parimutuel wagering on everything, including the five-entry pony race for children. In the half-mile Stock Horse race, Shelhamer, by then a teenager, raced his own horse, Brownie .Graduating from Bozeman High School in 1941, Shelhamer entered the military. His equestrian background initially placed him with the Army Veterinary Corps at the famed Fort Robinson, Nebraska remount center. He later became a pilot. While at Fort Robinson, Shelhamer served under Colonel Floyd Sager, who later became the resident veterinarian at Kentucky’s famous Claiborne Farm, birthplace of Triple Crown winners Gallant Fox and Omaha, later home to the famed stallion Bold Ruler and his greatest son, Secretariat. Sager and Shelhamer remained in contact over the years, no doubt sharing a lifelong interest in racehorses.

Returning home after World War II, Shelhamer rodeoed, competing in saddle bronc and steer wrestling events. In 1950, he married Jane Ringling. Her family owned the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, plus a substantial amount of Montana land. The couple raised six children, motivating Shelhamer to leave the rodeo arena for safer and more lucrative work.

One of Shelhamer’s ventures was raising racehorses with his father. But in the racing world of the early 1950s, parimutuel meets in Montana were down to three: Billings, Great Falls and Shelby. Finding few tracks to run his horses, Shelhamer built his own.

“Beautiful Mountain View”

In 1953, Lloyd and Jane purchased the Hacienda, a roadhouse near the intersection of Jackrabbit Lane and Highway 10. They renamed it the Beaumont, for “beautiful mountain view.” Shelhamer invested $250,000, excavated a half-mile oval and built horse barns. He created the most glamorous and modern racetrack in Montana, and the only track in the state not part of a county fairgrounds.Promoting the facility as offering “Kentucky Derby–style racing,” he installed an electrically operated starting gate and a photo-finish camera. He built a covered grandstand that held 1,500 people. The roadhouse was remodeled into a modern nightclub and restaurant with two bars. Shelhamer insisted that nothing prevent patrons in the clubhouse from watching the races, installing 160 feet of glass windows.

The Beaumont Club opened Memorial Day weekend, 1954. It was a hit. One-hundred-seventy horses arrived, including entries from California, Arizona, the Dakotas, and Wisconsin. Running races through the Fourth of July, the Beaumont averaged 2,500 visitors a week, and on the third weekend of June, 4,500 people attended. The clubhouse, open from 8:00 a.m. until 2:00 a.m., offered a wine list featuring European vintages, and its “surf and turf” menu included lobster thermidor, Chateaubriand beef—and frogs’ legs. Evening entertainment featured bands from Las Vegas.

That winter, Shelhamer also brought cutter racing to Montana. In the 1950s, racing cutters were often home-crafted half-barrel “chariots” welded onto runners, pulled over snow by two-horse teams. Not the most stable design ever concocted, and advertising for “chills, thrills, and spills” was accurate. In February 1955, the Beaumont meet was a prep for the national cutter racing championships in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and drew twenty-five teams. Shelhamer even entered his own horses, R No-Gough and Dutch S.

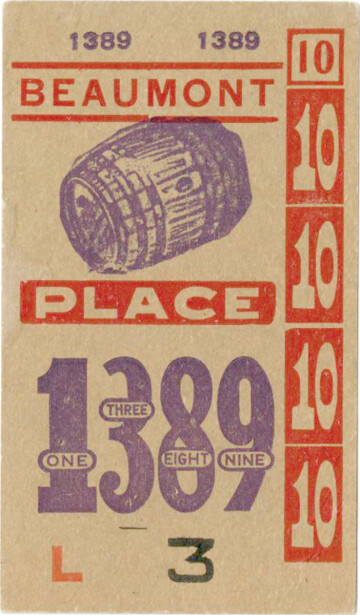

Even though electric equipment displayed racing odds in real time had been around since the 1930s, the 1954 Beaumont meet had racing odds put up on a chalkboard, with old-style preprinted parimutuel tickets sold to bettors. Mathematical calculations were performed by hand on spreadsheets. So Shelhamer needed one more thing for his “modern” track: an electronic totalizator system to calculate and display parimutuel odds, betting pools, and payouts. So he went to Chicago and bought a used Totalizator system with an electronic display (“tote”) board.

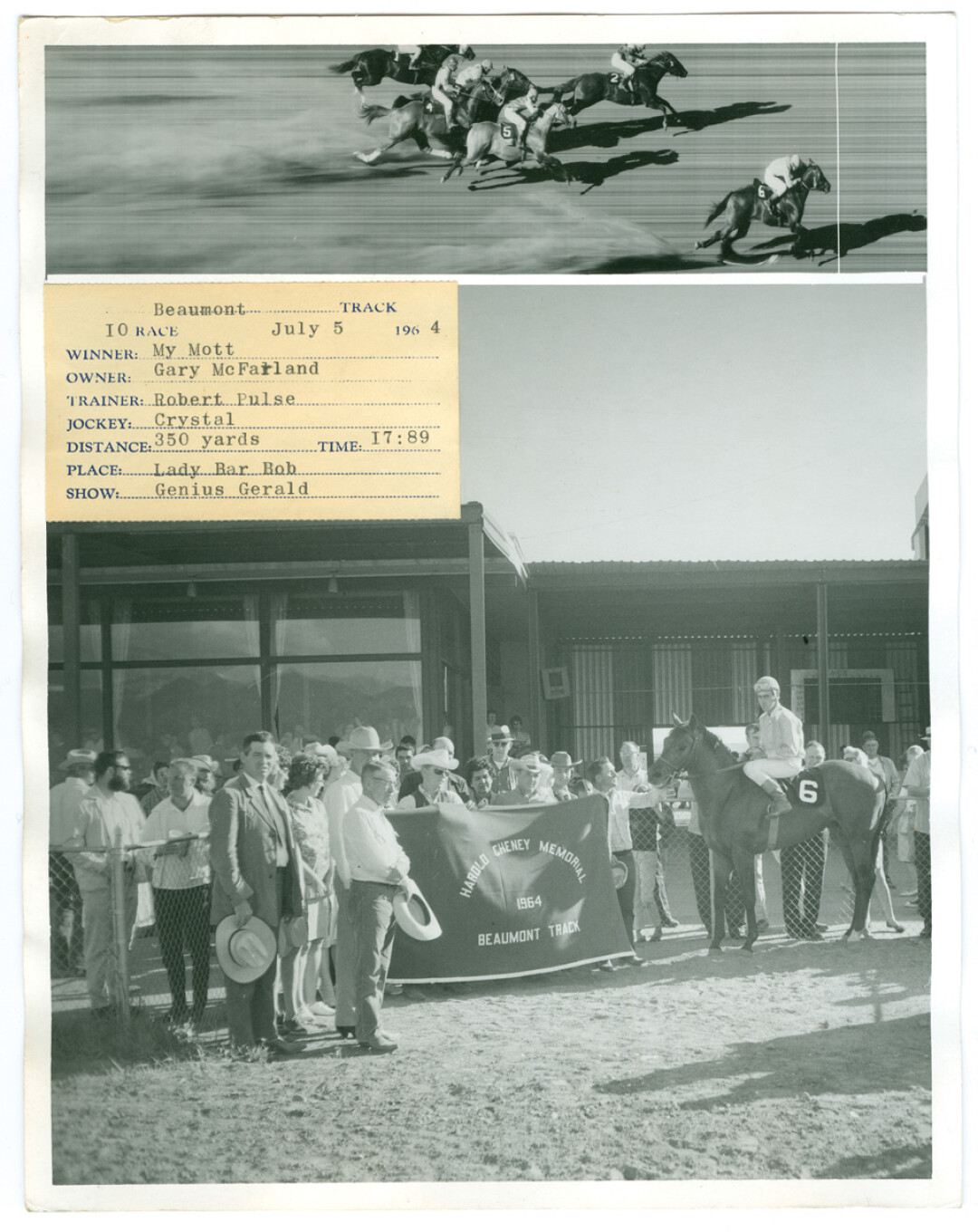

The electric tote board debuted in 1955. That year, the American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA) evaluated the track and approved the meet. This allowed the Beaumont’s Quarter Horse races to become part of a horse’s official record. Horses came in from out of state and ran in front of large, enthusiastic crowds. In the 1960s, Quarter Horse numbers were strong, especially because the large tracks at Billings and Great Falls often ran Thoroughbred-only meets. In August 1964, the Beaumont hosted a race with one of the largest purses ever offered in the state up to that time—$70,000.

United Tote

Gallatin County alone lacked the population to support the track and club year-round, and the Beaumont struggled. Before interstates came through Montana, out-of-town visitors had to travel long distances on two-lane highways to get to the track. While today, Gallatin County is a popular tourist destination, Shelhamer later said he was ahead of his times. He believed that had he started the facility 20 years later, it would have succeeded as a resort-style destination.

Finding it a challenge to keep the Beaumont profitable with races only offered a few weeks each year, Shelhamer looked for outside revenue and found it at other tracks. He realized that Montana race meets were expanding, and everyone wanted wagering. With a mobile tote board and a team who could calculate payouts, Shelhamer and his staff began to travel. He managed some of the smaller county fair meets, at times even called races. Shelhamer was a hero to local fair boards, giving many small Montana tracks a kickstart. In his own way, Shelhamer helped launch Montana’s second “golden age” of racing.

In 1957, he named his company United Tote. The company grew along with Montana racing. By 1966, the newly formed Montana Horse Racing Commission approved dates for fifteen tracks, and many used Shelhamer’s equipment and expertise. United Tote expanded beyond Montana to ten other states.

With expanded business came regulatory trouble. Shelhamer’s antiquated equipment produced inaccurate payouts. Reports to the 1969 Montana Horse Racing Commission revealed problems with mechanical failures and calculation errors. There were overpaid and underpaid parimutuel tickets. United Tote properly paid out 80% of the handle to bettors, but tallies were off by hundreds of dollars in both directions—winning tickets paid both larger or smaller payouts than they should have. Posted odds sometimes changed after races started, and errors showed up in past performance charts.

That year, Governor Forrest Anderson appointed a “tough new commission” that included horse trainer and University of Montana law professor Larry Elison, tasked to “shape up operations.” Elison crossed swords with Shelhamer. As rumors flew, the Commission asked the county fairs to “hold off on contracting” with Shelhamer for the 1970 season while they investigated. They set up a hearing in January 1970.

At the meeting, Shelhamer attacked. Bringing in three lawyers and many fair board supporters, Shelhamer’s contingent faced off against Elison in a five-hour “free for all.” The commissioners outlined the problems of United Tote, only to be questioned on their own financial dealings and accused of trying to put Shelhamer out of business. At one point, someone demanded the entire commission resign and Elison was asked point-blank if he was a relative of the Governor (he was not). After defending himself and the commission’s work, Elison hit back. “We’ve been rocking the boat. It’s quite apparent the boat is not wanting to be rocked in any regard.”

The unspoken problem was that the regulations governing Montana parimutuels were inadequate. Elison could only conclude the investigation by stating that that the Commission was “most certainly” going to regulate horse racing, but for the time being, fairs now had the information they needed to “make their own decisions” about which parimutuel contractor to hire. The Commission issued its annual report a month later, suggesting updated rules and regulations to avoid future problems. Chair Norman Kalbfleisch wrote, “The Commission has encouraged forceful and honest control of racing for the protection of the public.”

Shelhamer stayed in business, and after fending off another round of regulatory trouble in 1973, he quietly improved his operations. To do so, the company started manufacturing its own equipment and leasing some of it to other vendors. By 1979, Shelhamer’s children became active in the company, and United Tote went “high tech,” becoming the first Totalizator corporation in the USA to computerize its systems.

Back at the Beaumont

As United Tote took off, Shelhamer still had problems with the Beaumont. The supper club did well, but the racing side had trouble. In order to have frequent races to draw in visitors, individual race purses were low—and racehorse people could not survive on $100 a race, split between the top four finishers, jockeys, trainers and owners. Low purses led to fewer entries, which led to fewer spectators and reduced betting handle, a vicious spiral to the bottom.

Shelhamer sold the club and the track in 1967. While the supper club periodically remained open under different ownership, eventually it was torn down and land subdivided. Belgrade today has Triple Crown Road, Quinella Street, Show Place and Secretariat Street near the high school. These streets outline the general vicinity of the Beaumont track. Businesses on West Main Street are built on land that once housed the clubhouse and parking lot.

Soon after the Beaumont closed, Montana’s new 1972 Constitution went into effect, allowing gambling “by acts of the legislature or by the people through initiative or referendum.” With it, racing days exploded. By 1982, fourteen tracks in Montana held over 140 days of racing—pushing the climate edges of Montana’s short summers—and pulled in annual parimutuel handle of almost $12 million. Legally approved race days in Montana peaked at 143 in 1984. That year, the Shelhamer family took United Tote public, and by 1986, annual earnings were close to $10 million. At that time, United Tote controlled 65 percent of the market for parimutuel equipment. Shelhamer’s dream of racetracks as resort-style destinations was also coming to fruition: He owned Sunland Park Racetrack in New Mexico and was the majority owner of the track in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. In 1994, Shelhamer retired to his ranch in Shepherd, north of Billings. United Tote is still in business today, now a wholly owned subsidiary of Churchill Downs, Incorporated.

The Beaumont thrived for just over a decade, with glamour and ambition ahead of its time. Lloyd Shelhamer’s dream of high-class racing combined with his vision for United Tote and support of horse racing at small county fairs helped launch Montana racing’s second golden age. While 21st-century racing in Montana struggles, with only two race meets remaining, the call to the post and the roar of the crowd as a winning horse thunders down the stretch echos to a time when a Montana boy who loved cowboy boots dreamed of bringing the glamour of the Kentucky Bluegrass to the mountains of the Gallatin Valley.

Brenda Wahler of Helena is a fourth-generation Montanan with a lifelong interest in horses and history. She lived in Bozeman and showed horses in the 1970s and 1980s, when the racing community was a major presence at fairgrounds across the state. Today, she is an attorney and also operates an equine education and consulting business. Please join the Gallatin History Museum on October 2 for a presentation and book signing by Brenda Wahler. For more information visit gallatinhistorymuseum.org/events.

| Tweet |